SUMMARY

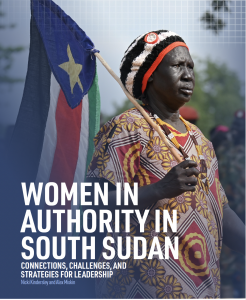

• Across South Sudan, women of different socio-economic backgrounds and experiences are fighting to take up positions of authority at all levels. This process is uneven, non-linear, and socially complex.

• The ways in which women are organizing for leadership and authority are linked between different parts of the country: from urban to rural spaces, across counties and states, and across social classes, from the neighbourhood water pump to national peace negotiations.

• Women working in urban neighbourhoods have made significant steps forward in organizing and gaining positions of authority over the last decade. These shifts are, however, not always accompanied by real shifts in power and equality.

• Women are significantly engaged in peace negotiations and mediation, especially in rural areas where they are active in the many local peace processes built over the last five years. Despite their involvement, their roles are often hidden. Moreover, their methods and representation are not reflected at state or national-level peace negotiations.

• There are fundamental economic and social barriers to women taking up authority. These include significant workloads at home and work, limitations of education and time, and the risks of social stigma and confrontation with the authority of male family members. These barriers are particularly acute for working-class, rural, displaced and disabled women but also act to block the abilities of educated and middle-class women to assert their authority.

• Property rights are a key barrier to women’s leadership. In both rural and urban areas, most women do not have the rights in practice to hold significant intergenerational wealth, especially in land and cattle, nor (therefore) to make decisions about this wealth. This fundamentally affects the abilities of these women to make decisions both within their family and in wider society about marriage, divorce, domestic and sexual violence, child custody and inheritance.

• The impact of nearly a decade of the political instrumentalization of ethnic difference in politics and conflicts at local and national levels is highlighted as a barrier to collective action. Women are not just divided by social and economic class, location, education, disability, age and experience, but also by anger, fear and prejudice as a result of nearly a decade of violent politics. They are further divided by different ideas and views of women’s priorities and strategies for leadership going forward into the future.

• The research highlights programmatic, administrative, and funding priorities for supporting women’s leadership work. Programme planning should provide for time and space to meet and develop leadership strategy and pressure campaigns across political and economic sectors. Basic material support is needed for infrastructure and tools, like bicycles, phones and community spaces, not just for organizational capacity but for respect and visibility.

• During research, women suggested more radical shifts in programming: for example, moving urban meetings and urban programmes to rural locations, and supporting boycotts of meetings or peace negotiations where there is insufficient or no women’s representation.

• Administrative and funding systems must work to support women’s efforts to gain and keep leadership power. Recommendations include: positive discrimination in development programme hiring; bias-challenging training with male staff, as well as robust processes for reporting and addressing sexual misconduct and misogyny; and funding sustained, long-term support for women’s economic and civil society organizing.