SUMMARY

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC, Congo), the opaque land governance framework, known to be at the bottom of countless conflicts ranging from disagreements between neighbours to violent clashes between armed groups, has been undergoing reform for more than ten years. Much policy attention in these debates around land and conflict is given to the Congo countryside but stakes in the city are just as high.

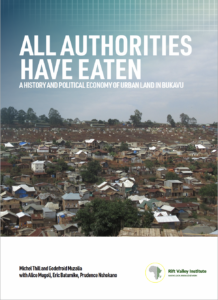

To better understand the land governance framework, it is insightful to explore the history and political economy of urban land in the eastern city of Bukavu. Three specific land conflicts are of particular interest: 1) the Ruzizi cemetery, where some people have been building homes ever since the Congo wars (1996–2003); 2) a wide open former parade ground in the Panzi neighbourhood, supposedly a public space home to both a football pitch and a contested army camp; and 3) Mbobero, a village on the outskirts of Bukavu that was drawn into the spotlight when the former president’s family acquired large tracts of land there. Policy considerations formulated in relation to these land conflict can serve to stimulate current donor discussions around land interventions and reform by offering unique angles and perspectives, from the ground up.

The research upon which this report is based points to two key patterns that shape current practices around urban land access and tenure. First, colonial land law and administration have created an urban sphere that is separate from the rural world. While land in Bukavu has remained at least legally distinct on paper, practices of land access and tenure have changed over the decades, at times rendering urban land law meaningless. Second, in the patronage-driven logics that began to permeate all state institutions in the Congo from the 1970s onwards, politics and business have become inherently intertwined. Wealthy political entrepreneurs are given favoured access to state institutions and resources in return for their loyalty. At the same time, low-level state administrators leverage their positions to secure their own income and provide kickbacks to those superiors on whom their jobs depend. In this context, urban land and property have become highly lucrative resources for all of them.

The experiences of those living and coping with land conflict in Bukavu speak volumes about the challenges these patterns create in their everyday lives. When asked how to address these challenges, what is most apparent in their responses is their loss of trust in the formal justice system, their preference for alternatively mediated agreements and their call for the state to take their side instead of that of the rich and powerful. These responses are couched in an overarching imperative to acknowledge people’s pursuit of dignity as reflected in their everyday struggles to make a home in Bukavu.

What does this mean for donors supporting land reform in Congo?

Find the French version of this report here.