The research for this blog found that locally led women’s microfinance groups provided financial security and opportunities for refugee women who could not get funds from banks or NGOs.

By Tamanji Logodi

Introduction

Originally a temporary home for South Sudanese fleeing war, Kakuma refugee camp now houses refugees from many countries in eastern, central and the Horn of Africa. By 2024, it was home to more than 280,000 people. Despite efforts by more than a dozen NGOs, however, extreme poverty persists, and refugees rely heavily on monthly food vouchers from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and World Food Programme (WFP).

Over time, the value of these Bamba Chakula vouchers has decreased, just as the number of refugees has grown.[1] This directly affects women, who often bear the burden of caring for their families.[2] Consequently, women are participating in savings initiatives as a means of survival and growth. Microfinance models, such as Village Savings Loans and Associations (VSLA) and Community Savings and Credit Groups (CSCG), have proven very effective in the camp.

The most common microfinance models in my recent study in Kakuma were CSCGs—self-selected groups of 15 to 30 people who come together on a regular basis, usually weekly, to borrow and save. These groups are very transparent; all their records and excess funds are kept in a box with three locks. Three members, chosen by the group, each keep one key. The box can only be opened in front of all members.

The study aimed at understanding informal and formal finance in Kakuma in order to explore how they interact. As such, it has important lessons for NGOs seeking to support women’s financial groups to improve livelihoods. It shows that informal groups run by refugees have created a loan system that works well due to its inherent local relevance. These groups have low default rates and strong trust among members. They help vulnerable people, including women, single mothers, unregistered refugees and very poor individuals. Having said this, these refugee-led groups often lack sufficient funds to lend their members and feel they do not offer enough training in business skills, livelihoods and financial literacy.

The study shows how refugees develop a measure of self-reliance, following interviews with 38 women in refugee-led savings groups, from a variety of livelihoods and backgrounds, and members from 2 NGOs and 4 other microfinance organizations, including banks. Additionally, I conducted focus group discussions and key informant interviews, and review of existing literature. 38 per cent of the women interviwed were South Sudanese, 30 per cent were Burundian, 22 per cent Sudanese, 5 per cent were Rwandan and 5 per cent were Turkana from the Kenyan host community.

In Kakuma, the idea of financial self-reliance emerges from the failure of the UNHCR interventions to help refugees achieve it over decades of support. Kakuma was opened in 1992. In 2024, the UNHCR, which works with other agencies, announced it would reduce its funding and food. It said it was running out of money because of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. This announcement caused great distress among refugees and there were three reported suicides that same month.

As a resident of Kakuma, I personally witnessed one such case. This involved a widow from Kalobeyei integrated settlement, 35 km from Kakuma, who hung herself from a tree. She had been borrowing from a shopkeeper and paying him back with Bamba Chakula funds. On the day she died, she and her five children had not eaten for three days. Desperate, she went to the shopkeeper. She was already three months ahead in her borrowing and, knowing that, on reduced ration vouchers, she would fall even further behind, he turned down her request.

Microfinance in the refugee context

Refugees come to the camp for various reasons—political conflict, severe hunger, betrayal and persecution. Hearing their stories helps you understand why they fled. Some refugees lose contact with their relatives, others stay in touch. When they need help, they might ask relatives around the world for support, but it can take days, weeks or even months to receive it.

When refugees first arrive at Kakuma, they go through registration processes and are either categorized as asylum seekers or fully recognized refugees. This distinction is critical: Asylum seekers are considered temporary residents and are not given refugee identification. Instead, they receive documents not widely recognized outside the camp. As a result, asylum seekers face many restrictions. They cannot attend Kenyan universities or leave the country because they lack IDs or travel documents, like the Conventional Travel Document (CTD) available to recognized refugees. Without IDs, they cannot access loans from banks, leaving them with limited opportunities for personal or economic growth. Even though they are ‘temporary’, many live in the camp for decades, missing out on education, work and other opportunities. Worse still, they have little hope of resettlement to third countries without an eligibility interview, the outcome of which can be positive or negative.

Fully recognized refugees have more access to opportunities. They can attend school outside the camp, access microfinance services, participate in international conferences and have a chance of being resettled in third countries. Even they, though, must go through bureaucratic processes for documents such as waiting slips, IDs or CTDs. The absence of valid documentation prevents several hundred million adults around the world from accessing financial accounts.[3]

Informal sources of support

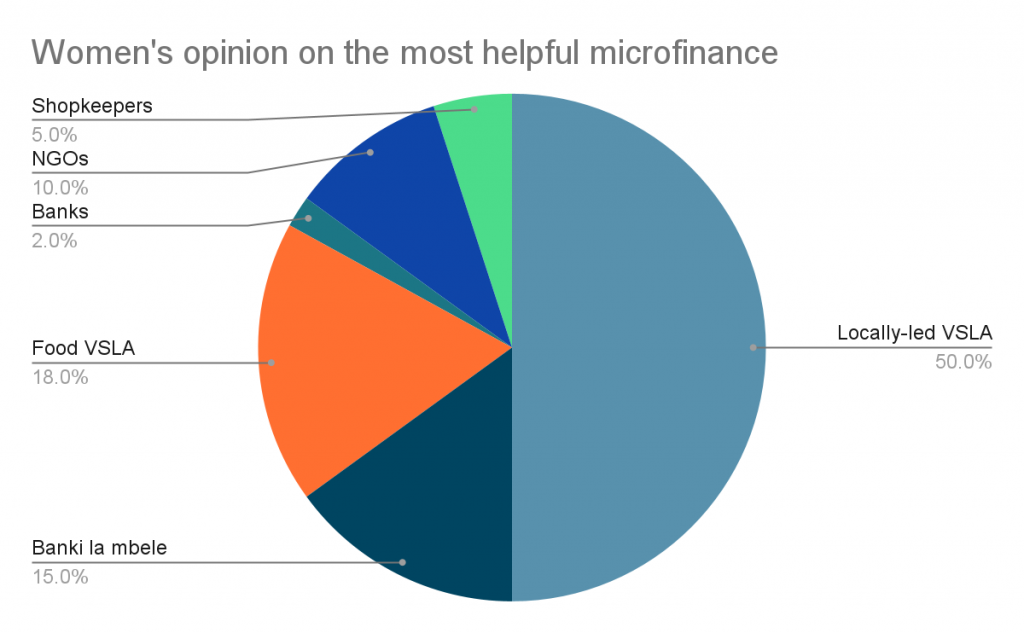

When I gave women the opportunity to single out the individuals and institutions that played roles in financial support, they first mentioned CSCGs, then others, such as shopkeepers, Banki la Mbele, NGOs and banks. Using a participatory ranking method, I drew a circle and allowed them to discuss these sources, allocating percentages based on which best served their most urgent requests. The pie chart below shows the women’s preferences and the outcomes of these discussions.

The results of participatory action research focus group discussions on 17 August and 1 September 2024.

Banks were rated the least helpful, described mainly as places to collect money sent from third countries, often through the Western Union. Only a few women had attempted to secure loans from Kenyan banks. A major barrier to this was not having a unique tax ID, the Kenya Revenue Authority PIN. Banki la Mbele is an informal way to borrow money from people in the community. Its main benefit is getting money quickly. Its lenders are not professional moneylenders, just individuals looking to earn interest. When you borrow from them, you often need to provide collateral and have a credible witness vouch for you. Such lenders are strict about repayment deadlines. If you miss one, they might take away your belongings, such as roof sheets.

Shopkeepers also play a key role in lending in Kakuma. They provide goods and cash to trusted customers and have become a source of hope. They are more likely to help if you are a loyal customer. Trust and reputation are crucial, and returning money on time affects future assistance. If two people borrow large sums at once, a shopkeeper’s funds are limited for others. Interestingly, sometimes customers don’t have to pay interest. It is up to them to show their appreciation.

It was clear how deeply women valued these informal community savings and credit groups (VSLAs and CGSGs). They spoke passionately about how VSLAs helped them prepare for financial emergencies. Women emphasized that trust was the foundation of VSLAs, which is quite different from formal systems of collateral, where the law fills the space occupied by trust. This flexibility and sense of community makes VSLAs highly effective for women facing financial shocks.

Majdalia Marius Kuku shared her experience with me during an interview in Kakuma 1: ‘My child got sick in 2022 and needed KES 12,000 (about USD 93) urgently for medication. I was able to borrow the money from our VSLA that same night.’ When time was of the essence, the VSLA delivered. Her child was treated and recovered. ‘Of course, we have rules, but they’re flexible,’ she said.[4]

Many women use loans from their VSLAs to start small businesses, such as selling food, handmade crafts or farming supplies. These, in turn, generate income that can be reinvested in the community, creating a cycle of development. Majdalia is a good example. She joined a Rotating Savings and Credit Association (ROSCA), where the money contributed by the group is given to one or two members at a time. When it was her turn, she received KES 30,000 and used it to start a food business.[5]

Formal sources of support

Women mentioned organizations such as BOMA, a US-based NGO; GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit); and Inkomoko, the largest lender to refugees in Africa, as sources of support. They see these as more formal. I found that when these two systems—informal and formal—work together, they can create opportunities for groups to succeed and expand their impact.

BOMA issues small grants to almost 10,000 Turkana and refugee women in Kakuma and Kalobeyei, while GIZ says it supports 30 per cent of the VSLAs it identifies. Laban Yaminikiza from GIZ says VSLAs formed by members of the same tribe or nationality are more likely to succeed. But VSLAs can build connections in culturally diverse groups, too, through common bonds between neighbours, co-workers or members of the same church.[6]

Such social cohesion is an important by-product of microfinance services, strengthening the union of the refugee community. Members of successful VSLAs can accumulate enough savings to invest in larger, more sustainable businesses. Some have even transitioned into Kenyan-style Savings and Credit Cooperatives (SACCOs), which offer more advanced financial services, including larger loans and the ability to purchase assets such as land or livestock. Their transformation highlights the long-term potential of microfinance in refugee settings.

About the author

Tamanji Logodi is currently pursuing a Master of Arts in Applied Community Development at Future Generations University, USA. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Theology and Community Development Outreach from Nation to Nation Christian University, USA. He also has a Diploma in Primary Education from Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya, and a Diploma in Early Childhood Education from Rongai Teachers Training College, Kenya. Additionally, he holds a University Preparatory Certificate from the OSUN Hubs for Connected Learning Initiative. Tamanji currently serves as a Business Mentor for BOMA NGO, supporting a poverty graduation model livelihood program in Kakuma, Kenya. He also serves as a Youth Advisory Panel Member for UNFPA, representing his county and advising on gender and child rights issues.

Acknowledgements

This paper has been published as a result of Tamanji’s training with the Rift Valley Institute’s (RVI) Research Communities of Practice (RCoP) project, a partnership carried out with funding from the Open Society University Network Hubs for Connected Learning Initiatives. It therefore reflects the views of the author and not the views or position of the Rift Valley Institute. RCoP is among several RVI flagship projects that support the professional development of early career scholars in eastern and central Africa through training, mentorship and the dissemination of research outputs. It is a value–driven project based on RVI’s long–term experience and presence in the region, built around a community of practitioners and academics with a common interest in the professional development of early career researchers. In the third phase of the project, RVI trained seven early career scholars from Kakuma refugee camp between May and October 2024.

This blog was edited by Catherine Rosemary Bond.

[1] J. Crisp. ‘UNHCR, Refugee Livelihoods and Self reliance: a brief history’, UNHCR, 2023. Accessed 11 October 2024, https://www.unhcr.org/publications/unhcr-refugee-livelihoods-and-self-reliance-brief-history.

[2] A. Jamal. ‘Minimum standards and essential needs in a protracted refugee situation. A review of the UNHCR Programme in Kakuma, Kenya’. Evaluation and Policy analysis unit, UNHCR, Geneva, 2000.

[3] G. M. Grandolini. ‘Five challenges prevent financial access for people in developing countries’. 15 October 2015. World Bank Blogs. Accessed 7 January 2025, https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/voices/five-challenges-prevent-financial-access-people-developing-countries.

[4] Key informant interview, Majdalia, Kakuma 1, August 2024.

[5] Key informant interview, Majdalia, Kakuma 1, August 2024.

[6] Key informant interview, Laban Yaminikiza, GIZ, Kakuma 1, September 2024.