The current conflict over the contested city of Lasanod has the potential to expand into a crisis affecting several of the Somali-speaking territories. This blog – building on research the author conducted in 2021 – looks at the conflict from the perspective of Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State (SRS), focusing on the humanitarian fallout and the disruption to trade and livelihoods.

On 6 February 2023, heavy fighting broke out in the city of Lasanod between Somaliland government forces and members of the Dhulbahante clan. The latter reject the incorporation of Lasanod into Somaliland and seek to establish an autonomous Khatumo State that would include the regions of Sool, Sanaag and Cayn, (collectively referred to as SSC). The contestation over Lasanod has a long history. The trigger for the outbreak of fighting in February was a conference of Dhulbahante Garaads (clan leaders) who agreed a 13-point declaration stating, inter alia, that the SSC regions are not part of the ‘separatist administration of Somaliland’. Fighting erupted between the Somaliland army and Dhulbahante clan militia and has continued sporadically, with hundreds killed and wounded and tens of thousands displaced.

Humanitarian crisis spills into Ethiopia

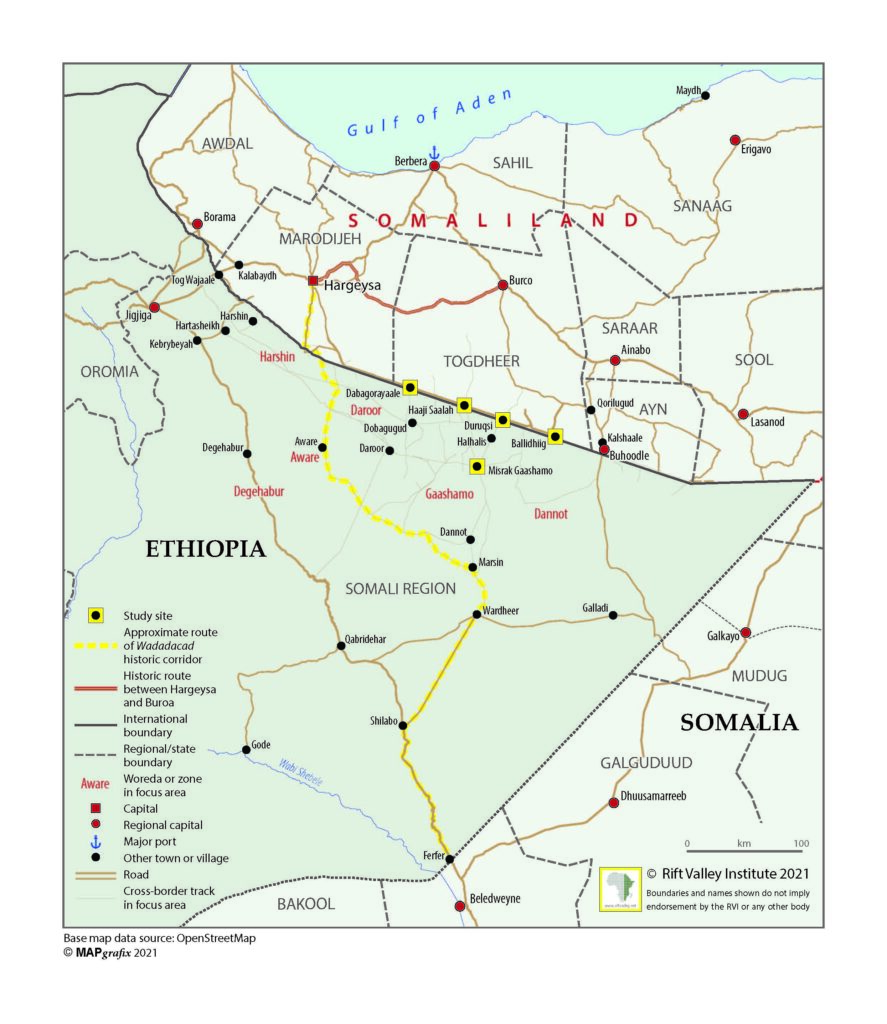

On 3 April, UNOCHA estimated that 100,000 people – mainly women and children – had fled from Lasanod into Ethiopia’s Somali region, settling in 13 locations in the Dollo zone (this is estimated to be more than half of the total number of people displaced by the fighting). Somalis have a long history of cross-border movement to escape conflicts and droughts, facilitated by social connections and the porous nature of the borders in the Somali-speaking territories. This was the case in 1988 during the conflict between the Somali National Movement (SNM) and Somali government forces in northern Somalia, which caused hundreds of thousands to flee from Hargeisa, Burao and Berbera to refugee camps in Ethiopia.

People escaping from the conflict are receiving little provision from the regional authorities in the SRS, and an international humanitarian response has been slow to mobilize and the UNHCR is appealing for additional emergency funding. The fact that both the SRS regional administration and humanitarian organizations were already overstretched supporting people affected by a protracted drought in the region, has also affected the response.

Hussein Ahmed, a trader from Wardheer (a town in Dollo Zone) who frequently travels to refugee receiving areas such as Galhamur, a small town about 20 km from the border, has explained how the local community is struggling to accommodate people who arrive carrying little or nothing with them: ‘In Galhamur, every family is hosting several refugee families in their homes. Some are forced to stay outside the town without shelter, cooking equipment or proper sanitation’. Since 2021, Lasanod’s economy has been largely cashless and people rely on mobile money transfers, but because they are now under a different network, they cannot access their money.

Trade disruption

The conflict has disrupted trade between Somaliland, SRS and some of Somalia’s federal member states, including Puntland, Galmudug, Hirshabelle and even parts of South West State. The armed confrontation in Lasanod has led to a reduction in trade via the town of Buhoodle, which normally connects Burao – the second largest city in Somaliland – to districts in eastern Dollo in Ethiopia and southern Somalia. This route is usually used as a convenient shortcut across the SRS for the traders heading to or from Somaliland. The goods traded include food, but also construction materials exported from Somaliland to the SRS and areas in central and Southern Somalia such as Galmudug, and Beledweyne in Hirshabelle state.

Mohamed Haibe, a truck owner from Jijiga who used this route for two decades, explained:

Fruits such as papayas, mangoes and bananas, as well as livestock [mainly camels but also sheep and goats], were regularly traded from southern Somalia to markets including Burao and Hargeisa. Instead of using the tarmac road through Galka’ayo [located on the border of Puntland and Galmudug], traders seeking to shorten the distance would travel from Mareerguun [a town roughly 20 km north-east of Dhusamareeb [capital of Galmudug] through the Ethiopian Somali region to Burao, the biggest livestock market in the Somali territories. They would then cross the border at Buuhoodle [a Dhulbahante-inhabited area controlled by the SRS’s special paramilitary units – locally known as the Liyu police – on the Ethiopian side]. Most of the fruit transporters then proceed to Hargeisa, while livestock is typically sold in Burao.

Ahmed Merhaba, a food distributor based in Hargeisa, explained in late-February that their operations have been curtailed since the start of the conflict. This is because trucks are unable to travel along their usual routes due to security concerns. According to Ahmed, conflict in this region usually has an impact on trading routes and, due to its polarizing effects, the parties involved are attempting to use trade activities as leverage over their opponents.

In this instance, vegetable and fruit traders in Hargeisa and Burao have indicated their willingness to import these products from Ethiopia using the main tarmac road through Togwajaale. Traders from the Harti clan have also indicated their willingness to shift their trade from Berbera port to the new Gara’cad port in central Somalia. Meanwhile, elders from the Hawiye clan in South Central Somalia have expressed concerns over the disruption of trade activities since livestock and vegetables that were destined for Hargeisa and Burao originate in Hawiye dominated territories in South Central Somalia.

Trade disruptions have occurred unevenly. Traders traveling from regions of southern Somalia, who typically pass through the Sool region and cross the border at Buuhoodle, have been the most affected. However, the livestock trade from eastern Dollo in the SRS has remained largely unchanged. This is because the trucks cross the border using the Gaashaamo route in an area that is inhabited by the Isaaq clan, the dominant clan in Somaliland. Seeraar Abdillahi, a well-known elder and former livestock trader of the Ogadeen clan, based in Dollo zone, explained that:

Livestock trading is a vital source of livelihoods for many communities, and those in the SRS have particularly close trade ties with those in Burao. In contrast, traders from the central and southern regions of Somalia are uncertain about the situation on the ground and lack trust that they will receive their trading goods and trucks back if they are looted.

Trade across the Somali borders remains predominantly informal, lacking any formal process such as bank guarantees or letters of credit, and operates primarily through clan networks that facilitate the flow of goods across the region. During times of conflict, the trade activities are inevitably impacted.

Risk of disharmony across Somali territories

As well as the immediate disruption to trade, and the refugee crisis, there is also concern that the conflict over Lasanod could spill over into other parts of the Somali-speaking territories, including the SRS, due to the clan connections on either side of the border. Seeraar Abdillahi explained that while trade with Somaliland via Ballidhiig – a crossing point in the Gaashaamo district of the SRS (to the west of Buuhoodle) – has continued, he is concerned that this conflict could spread across the border if the situation is not resolved in the coming weeks. This is because the Isaaq clans in the SRS (mainly supporting Somaliland) and the Dhulbahante (mainly supporting the uprising) share territory and have a history of inter-clan conflict.

There have also been some signs that the relationship between authorities in Hargeisa and Jijiga (capital of the SRS) is being strained by the conflict. In December 2022, Dhulbahante leaders held a conference in Jijiga, shortly before the unrest started in Lasanod, leading some officials in Hargeisa to see the conflict as having been orchestrated within the SRS. The charge was denied by SRS president Mustafe Omar. On 9 March, the Somaliland government claimed that Liyu police from the SRS had taken part in the conflict over Las Anod – an accusation also firmly rejected by the SRS regional government.

In addition to the dire humanitarian impact, the conflict in Lasanod is having serious economic consequences across the Somali territories, demonstrating the interconnectedness of the communities and economies in this region. The informal and fluid nature of trade between Somaliland, Puntland the SRS and other Somali regions is often seen as an advantage in smoothing the passage of cross-border trade across the region’s international and federal borders. Conflict disrupts the trust-based nature of the system affecting the economy and livelihoods of communities in these border regions. However, the reliance on trust between different clan groups can also be a vulnerability during times of conflict.

This blog is a product of the UK government’s XCPT (Cross-Border Conflict, Evidence, Policy and Trends) research programme.