On Wednesday 15 November 2017, Eye Radio and the Rift Valley Institute aired the third radio show about the South Sudan National Archives, in coordination with the South Sudan Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports and UNESCO, with Norway’s financial support.

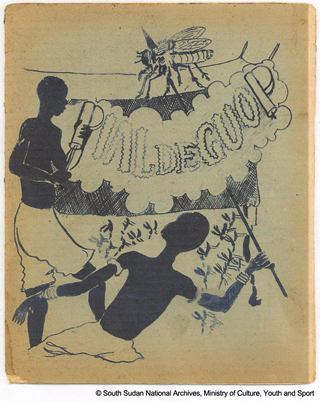

The show was hosted by Rosemary Ochinyi and looked at a document preserved through the work of the National Archives, the illustrated cover of a 1948 instructional health manual titled Pial de Guop, or ‘Good Health’ in Dinka. It was distributed among the Bor Dinka community in what was then known as Upper Nile province.

The two speakers invited to discuss the historical context of this document were Dr Julia Aker Duany, Vice-Chancellor of Dr John Garang Memorial University, and Dr Angok Kuol, Minister of Health, Jonglei State. Mr James Lujang from the National Archives also joined the show to talk about his work as an archivist for the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports.

Rosemary Ochinyi asked her guests to describe the context in which this health manual was distributed. What were the health issues facing the region in the first decades of the twentieth century? How did the colonial power reach out to the Bor Dinka people and introduce them to modern medicine?

Rosemary Ochinyi asked her guests to describe the context in which this health manual was distributed. What were the health issues facing the region in the first decades of the twentieth century? How did the colonial power reach out to the Bor Dinka people and introduce them to modern medicine?

‘This manual was a mean for the colonial government to try and educate people, to promote new ways of protecting their health,’ said Dr Kuol. ‘The most striking disease’ at the time was small pox, and outbreaks of malaria were frequent, ‘but we don’t have records because most of the population was living far away from the colonial centres of attention.’

One of these ‘centres of attention’ within the Bor Dinka community was the Malek school, built by missionaries at the beginning of the twentieth century. The school facilitated colonial access to the Bor Dinka community, as opposed to ‘the rest of the Upper Nile region, where access remained an issue’ according to Dr Kuol. The Malek school started to host a health facility in the 1930s, allowing the Anglo-Egyptian authorities to reach out to populations who, until then, relied solely on traditional medicine. ‘They started by treating the ruling elite, elders and chiefs, and persons surrounding them, not the community as such,’ said Dr Kuol. But gradually, ‘people around started to come in contact with modern ways of treating diseases.’

Dr Julia Duany elaborated on the challenges faced by the colonial authorities in their attempt at promoting modern healthcare. ‘At the beginning—and it is not only the Dinka Bor or the Upper Nile region—the encounter with the outside was really resisted by our people, because the first encounter with the white people or the Arabs was slavery. Nobody could really have trust in people coming from outside … So at the beginning, this modern medicine scared a lot of people.’

Language was also a barrier. Until the colonial authorities could communicate through indigenous languages, ‘the level of suspicion remained very high.’ Dr Duany recalled an anecdote told by her father, about a misunderstanding due to a mistranslation, ahead of a vaccination campaign in the Bentiu area. The interpreter reportedly said the injections would sterilize people, provoking panic and failure of the campaign. ‘People thought that this was meant to prevent them from having children!’

The pastoralists of the Bor Dinka community became more trustful after witnessing the benefits of modern medicine not only on people around them but also on their cattle. ‘The first time the Dinka of Bor started to believe in modern medicine was when they saw their cows being given vaccines. The disease-related deaths were reducing, their cows were multiplying … That gave them confidence that the modern way of doing things was actually improving their life rather than hindering whatever they had wanted.’

According to Dr Duany, it is only in the 1940s that the Bor Dinka started to embrace modern medicine, and ‘that is why these documents were coming out officially from the government and were now being spread around to the people. And also the missionaries began to train local people so that they could be able to explain it rightly to their own people.’ The progressive enrolment of children in school would also play an important role.

The two guests discussed traditional healthcare methods among the Dinka pastoralists and the natural mosquito repellents used in cattle camps—burning herbs to create smoke and cow dung ashes applied on the skin. Especially the latter is iconic of cattle camp imagery. ‘When it is really thick on your body, it’s very hard for a mosquito to bite you,’ said Dr Duany.

In the Bor Dinka community, herbs and roots were also used to prevent and cure malaria. The speakers stressed the importance of preserving this knowledge of medicinal plants. For Dr Kuol, part of the reason why this knowledge is currently ‘at minimum level’ is the way it was transmitted by traditional healers. ‘It wasn’t communicated to the people on a wide scale. They believed it is a family thing, and even among the family, it must be inherited, therefore you will teach only one of your sons, either the first born or the last born.’

Dr Duany added that with young generations leaving the countryside to come to the city, this knowledge was endangered. But she described how this herbal medicine is still known and used, even in the capital Juba. ‘You see many people go to the doctor and they still go to the market to buy this traditional medicine,’ in places like Konyo-konyo. She advocated for the universities of South Sudan to ‘research and upgrade’ this traditional medicine. This was seconded by Dr Kuol, who proposed the creation of a ‘medicinal plants research centre … to research the knowledge of these traditional healers and document medicinal herbs … In the future, treatments could be produced in South Sudan.’

Dr Kuol explained that since the publication of the 1948 health pamphlet, small pox was eradicated, which was ‘a revolution for modern medicine at large.’ More recently, the eradication of guinea worm disease was ‘also a message [to the youth] that yes, it can be done.’ He highlighted the new health challenges facing Jonglei State, such as endemic cholera outbreaks, HIV/AIDS and malaria, which is still ‘the number one cause of mortality in South Sudan.’

Dr Duany concluded by pointing out the importance of the archive document. ‘It is good to know that these things started very long time ago. This now can help us plan our future.’ She appreciated the work accomplished by the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports to preserve this knowledge. ‘When people say that South Sudan is a very young nation, I always dispute that. We’re not that young not to have our own history and our own knowledge.’

The National Archive

Mr James Lujang, an archivist at the National Archives, gave some insights into the preservation project which started more than ten years ago. The files were ‘scattered’ between the Muderia, the location of the former Central Equatoria State in Juba, and Juba Girls Secondary School. ‘In 2007, we collected these files. They were in sacks. We took them out of the sacks, we catalogued them, and we brought them to the conservation site.’ The documents ‘were really damaged, [but] now they are kept properly.’ He described how the archives staff were specialized in handling very old and damaged documents—the oldest dating back from 1902 according to him—and in digitizing them for enduring preservation.

He admitted that not everyone understands the importance of the archives. A friend once asked him ‘why are you working in this dusty place with these old papers?’ He responded, saying that ‘we are struggling for our nation, because when you work for the archives, you really want to show our people our history as South Sudanese … The archives are not for the old people, they are for the young generation, they are for the researchers … They are telling us about where we come from. No country without a history. A country without a history, that is not a country.’

The next radio show will focus on the archive document ‘An Appeal by the Peace Delegation to the Anyanya’ from 1967 and will take place on Wednesday 22 November 2017, at 16:00 EAT on Eye Radio (98.6FM).

مشروع دار الوثائق الوطني

تاريخ تانا – (تاريخنا)

في اطار توثيق تاريخ جنوب السودان عبر حلقات إذاعية يسلط الضؤ عن دار الوثائق الوطنية في البلاد

تقرير: فلورانس ميتوكس

ترجمة: فرانسيس مايكل

في الخامس الخامس من نوفمبر الحالي تم مناقشة وثيقة تاريخية حول ادخال واستخدام الطب الحديثة في مدينة بور من قبل المستمعر، وهذا مواصلة لبرنامج التوثيق عن تاريخنا في جنوب السودان، التى تقوم بة المركز القومي للوثائق (تاريخ تانا – تاريخنا).

تناول الحلقة الوثيقة التاريخية عن علاج مرض ملاريا في منطقة جونقلي والتى تعود تاريخها لعام 1948 وهي وثيقة عن الصحة العقلية ومعالجة مرض ملاريا، في إقليم اعالى النيل سابقا.

تحدث في الحلقة كل من الدكتورة جوليا أكير دوني نائب مدير جامعة الدكتور جون قرنق، والدكتور انقوك كوال وزير الصحة بولاية جونقلى، والسيد جيمس لوجانق من مركز القومي للوثائق.

في حلقة النقاش عبر أي راديو، تم طرح السؤال من مضيفة الحلقة روزميري اوشاني عن القضايا الصحية اي الامراض التى كانت واجهت الاقليم في القرن العشرين؟ وكيف وصل الاستعمار الى دينكا بور لشرح عن الطب الحديث؟

يقول الدكتور كوال وزير الصحة الولائي ان هذا العملية كان بهدف محاولة تثقيف الناس صحيا، وتعزيز طرق جيدة لحماية صحتهم، وان المرض الاكثر انتشار في ذلك الوقت هو مرض الجدري وملاريا ولكن ليس هناك اي تقارير او احصائيات حقيقية، بسبب ان معظم المواطنين كانوا يعيشون في أماكن بعيد عن أماكن تواجد المستعمر.

ويقول كوال ان واحد من المراكز داخل مجتمع بور هو مدرسة مليك والتى تم بناءها من بواسطة المجتمع المحلي من قبل الإرساليات في بدايات القرن العشرين، وان المدرسة كان يستخدمها المستعمر لتقديم الخدمات لمجتمع دينكا بور، وهي في اقليم اعالى النيل، لكن ظل تحديات تواجه تقديم الخدمات، ويقول الدكتور ايضا أن المدرسة بداء استخدامها كواحد من المرافق الصحية في الثلاثينات القرن العشرين، وبالتحديد 1930 ميلادية، وسمحت انجلو (سلطان) للسطات المصرية للوصول الى السكان الذين كانوا لايزالون يستخدمون العلاج التقليدي، قام المجموعة بتقديم العلاج للسلاطين والقيادات الاهلية في المنقطة وكل من كان حولهم وهذا ليس مجتمع دينكا بصورة عامة، وان الناس بداءت تفهم ويتوافدون من اجل تلقي العلاج الحديثة في تلك الوقت.

وتقول الدكتور جوليا نائب مدير جامعة الدكتور جون قرنق في المداخلة، ان الاستعمار واجهت تحديات من قبل السلطات في جونقلى من أجل إدخال طرق العلاج الحديثة في بداياتها وهذا ليس دينكا بور فقط او إقليم اعالى النيل بكل الجميع ناصلت من اجلها، وهذا كان صدمة غير متوقعة من قبل السكان المحلين، السبب هو ان اول صدمة التى كانت مع الرجل الابيض (خواجه) او العرب كانت تتعلق بتجارة الرق، وبتالي لا يوجد شخص يثق في الشخيصات التى تاتي من الخارج، وبتالي خاف الكثير من الناس من العلاج الحديث واصيبوا بهلع.

وتضيف الدكتور جوليا ان مسالة اللغة كانت واحد من التحديات، حيث كان سلطات المستعمر تتحدث بلغة غير مفهومة، حيث ان كان مستوى الشكوك عالية بينهم، وتحكي الدكتور جوليا قصة حكها لها والدها عن سؤ التفاهم بسبب الترجمة الخاطئ، والقصة عن حملة التحصين في بانتيو والمخبر كان يقول إن إبرة التحصين سوف تصيب الناس بحالة العقم، وهنا تخلف الناس عن التحصين لان الفكرة كانت ان هذا سوف يمنعهم من الولادة اوإنجاب الأطفال.

وتابعت الدكتورة أن ثقة السكان في بور عادت بعد ان عرف الناس منافع العلاج الحديث، وان هذا ليس للناس فقط حتى الابقار لديهم العلاج، وتضيف ان أول مرة يؤمن به السكان في بور بالعلاج الحديث هو عندما بداء المستمعر في تحصين وتقديم العلاج للابقار بتحضينهم ضد الامراض التى تقتل الابقار وان ذلك أدت إلى تراجع موت الابقار وكان صحتهم جيدة، هذا ما زرعة فيهم ثقة كبير ان العلاج له دور مهم في حياتهم عسكس توقعاتهم.

وتضيف جوليا، ان في عام 1940 ميلادية بداءت دينكا بور في استخدام الطب الحديثة، وهذا سبب تواجد هذا الوثيقة من قبل الحكومة في تلك الوقت، وتقول جوليا ان ارساليات بداءت في تدريب السكان المحليين حتى يقومو بشرح وتثقيف السكان المحليين بالحقائق، وتشمل ذلك التوعية عن اهمية تسجيل الاطفال في المدارس.

وناقش الضيوف ايضا العلاج التقليدي عند مجتمع بور دينكا، وكيفية يتم محاربة البعوض وتشرح الدكتور ان ذلد يتم في مراعي الابقار، عن طريق اشتعال الدخان باستخدام مخلفات الابقار ويمتلى الأجواء بالدخان وبتالي يكون حول الشخص كلها دخان ومن الصعب ان يلدغ البعوض شخص في وقت التى تكون الجسم محاط بالدخان.

تقول الدكتورة ان في مجتمع دينكا بور، يستخدم الجذور والاعشاب في علاج مرض ملاريا، أن هذا الطريقة هي مبتكرة من السكان المحليين، وهي طريقة شاسعة وواسع الاستخدام من الناس المحليين وهم يؤمنون بها على اساس انها لها علاقة بالارث (موروثة)، حيث يكون هناك شخصات ورث طريقة العلاج من الاسرة ويقوم الشخص بتدريب واحد من ابنائها لتوريثه سواء كان بكر او اخر الولادات الاسرة.

وتضيف أن رغم هجرة الناس من القرى الى المدن لاتزال هذه الادوية البلدية مستخدمة حتى الان وهي مستخدمة حتى في العاصمة جوبا، وان بعض من الناس يذهبون الى الاطباء لكنهم لايزالون يذهبون لسوق من اجل شراء هذا الادوية البلدية، مثلا في سوق كونجو كونجو، ودعت الدكتورة المواطنين والمختصين من اجل اجراء البحوث في هذا المجال وتطوير هذه الادوية البلدية، وهذا مع وامن عليه الدكتور كوال والذي تقدم بمقترح على ان يتم تاسيس مركز للابحاث الطبية عن الادوية، من اجل اجراء البحث عنها ادوية (الجزور و الاعشاب) من اجل تصنيع ادوية في جنوب السودان بالمستقبل.

ويوضح الدكتور كوال، ان منذ عام 1940م لاتزال هناك امراض موجود مثل الجدري ودود الفرنديد، في ولاية جونقلى وهذا رسالة للشباب على ان يمكن محاربتها، وكاشفا ان اكبر تحدي الجديد الذي يواجه ولاية جونقلي هو مرض كوليرا والايدز وملاريا وهو من مشاكل منشترة في جنوب السودان.

وتختتم الدكتورة جوليا حديثها أن أهم شي في الوقت الحالي لمركز الوثائق الوطني، هو يعرف الناس ان هذا الاشياء بداءت منذ فترة بعيد ويمكن يساعد في التخطيط عن مستقبل واشادت بدور المركز والعمل التى تقوم به بدعم من وزارة الثقافة والشباب والرياضة، في وقت الذي يقول فيه الناس ان جنوب السودان دولة وليدة، وتضيف انا دوما اقول اننا لسنا امة جديدة ويجب ان يكون لنا تاريخنا.

ومن مركز الوثائق القومي شارك في الحوار الاذاعي ايضا جيمس لوجانق والذي تحدث عن المشروع والمركز وعلى ان المركز بداءت قبل أكثر من عشرات سنوات من الأن، وأن عملية جمع الملفات بداءت في مديرية مقر ولاية استوائية سابقا، ومدرسة جوبا الثانوية بنات، عام 2007، ويضيف ان هذا الملفات كانت مهملة وتم اخزها من مكانها وضعها في مكان أمن.

ويقول لوجانق، كان هذا الملفات حصلت فيها تلف كبير، لكن حاليا تم حفظهم في مكان أمن، وتعامل مع الملفات القديمة بالحذر وقتها، ويقول لوجانق أن ليس كل شخص يفهم أهمية هذه الملفات وأهمية التوثيق، ويحكي لوجانق ان ساله صديق لماذا انت تعمل في مكان وسخ وفيها ملفات غير نظيفة؟، وكانت الاجابة نحن نناضل من اجل الامة وهذا يعني عندما تعمل في الارشيف هذا يعني انك تريد ان تعلم الناس عن تاريخهم، والارشيف ليس للناس القدامى انها للجيل الجديد ولايوجد دولة بدون تاريخها وهذا من اجل ان لا نتعرض لسؤال من أين نحن؟

في الحلقة القادم سيناقش الحوار مسودة اي نداء محادثات السلام والتى تم تقديمها للانيانيا عام 1967 ميلادية.