A Hungarian researcher in Juba explains how a sixty-year-old letter in the National Archive of South Sudan led him to a prescient piece of reportage by Wolfgang Langewiesche, an American journalist of the 1950s.

…I reached the last pages of a dusty and never-opened file in the National Archive of South Sudan when I found this letter. The aging generator was loudly puffing in the courtyard… I opened the file titled Upper Nile Province 49.B.2. Vol. II (“Passports, Visas, and Permits to Enter Southern Sudan”)…. On the last page, a guy was…addressing the colonial administrator as you would your best man days before your wedding. Surely an American, full of self-confidence and money…

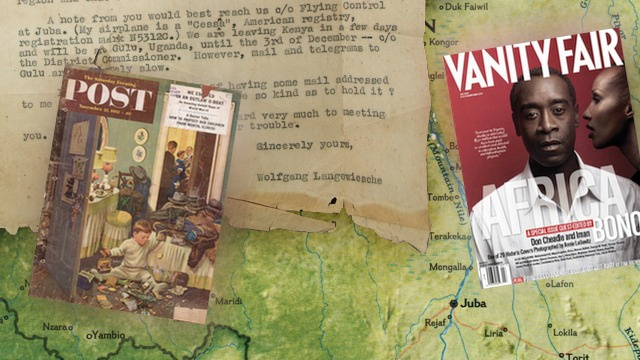

Wolfgang Langewiesche’s article… based on [his] visit to Sudan… entitled “What’s All the Noise on the Nile?”… appeared in the November 22, 1952 issue of the Saturday Morning Post, the Vanity Fair of the Fifties… The article is about the water struggle between independent Egypt and the British Empire, and the joint effort of the two powers to dig a 200-mile-long canal through the infamous Sudd, the South Sudanese marshlands, “a big attempt to crank up a backward region”… “a land of nothing—endless plains, thornbush, near-desert, earth-colored villages; heat, dust, glare” inhabited only by the “naked primitive”. Colonial language at its best.

Then suddenly, in the last few paragraphs, the argument supporting the canal collapses. Wolfgang Langewiesche sees something from the cockpit of his little Cessna (American, registration number: N5312C) that almost no one dared to see in his time; the canal will also kill and destroy. Colonization kills. Modernization can kill:

[I]f the Sudd Canal is dug, what is to become of the tribes that live in the Sudd—the Shilluk, Dinka, Nuer? Those people… live by the very thing the canal is designed to stop—the spilling of the Nile. They are cattle people who love their cattle… they love cows the way the Greeks loved beauty or the Americans liberty… I waded around a bit in the Toich with a research team of Britishers who were seeking a new way of life for those people. But they were baffled… If people are to live there, that’s how they have to live.

The Juba Archive and the 2,500 boxes of irreplaceable documents [including the letter that led to this paragraph] are in danger. Despite the spirited local staff and the considerable efforts of the Rift Valley Institute, UNESCO, the Norwegian Government, and the South Sudanese Ministry of Culture, future funding is uncertain. There is almost no money for wages, for petrol to feed the aging generator, not even for the rent of the place where the documents are kept. There are splendid plans for a new building—although without shelves or reading rooms—but construction hasn’t started yet. And donors keep saying that in the country with the highest maternal mortality rate, non-existent infrastructure, tribal conflicts, and no electricity in the grid, they have more important things to focus on. It is true, there is a lot of development and modernization to do. But without the Archive, we miss the chance to see this very development in a historical context. South Sudan may be the youngest country on earth, but it is not without history… We can learn from the failures of the past, but for that, first of all, we have to save the Archive.