The Rift Valley Institute works in partnership with the Ministry of Culture, Museums and National Heritage (MoCMNH) on the preservation and digitization of the South Sudan National Archives (SSNA). Under the current project, funded by the Government of Norway, through UNESCO, various activities are underway to showcase the information available in the archives to a wider audience. RVI and the MoCMNH are collaborating on a range of outreach activities including radio shows (Tarikh Tana), school study and discussion projects and social media outreach.

Zoe Cormack is an anthropologist and a historian who has done extensive research in the South Sudan National Archives. She is working on a series of blogs to highlight the rich diversity of information available in the archives and the way in which that information can contribute to documenting South Sudan’s history. This blog reflects on what we can learn about the 1965 ‘Juba Massacre’ from the compensation claims detailed in files found in the SSNA.

***

The South Sudan National Archives (SSNA) contains thousands of files, a rich historical record documenting the colonial period, and (more patchily) the early period of Sudan’s independence. Sometimes a file will jump out at you: it is immediately obvious that its contents are unique, a precious record of a hugely significant historical event. One such file, numbered ‘EP 11 B 2’ is a collection of compensation claims, which were made by individuals whose homes were destroyed by the Sudan Armed Forces on 8 July 1965 in Juba.

Often called the ‘Juba Massacre’, this was a major moment in Sudan’s first civil war. Residential areas of Juba (Atlabara and Kator) were attacked and burned by the army. The official explanation, put forward by the Minister of the Interior, was that the violence was prompted by a threatened rebel attack on the military headquarters. But this version of events was quickly contested: one witness, for example, said that it started as a quarrel between a nurse and an army officer. The number of casualties is uncertain, but the historian Deng D. Akol Ruay estimates there were between 1000 and 3000 deaths.1 Even at its lower end, this is a staggering number. For context, a housing survey by the Regional Ministry of Housing and Public Utilities in 1964 estimated the population of Juba was 19,763.2 Just days later, 76 people were killed when the army attacked a wedding party in Wau. The nature of these attacks, which fell heavily on educated and professional people, have been interpreted as evidence that the army was deliberating targeting the southern political class.3

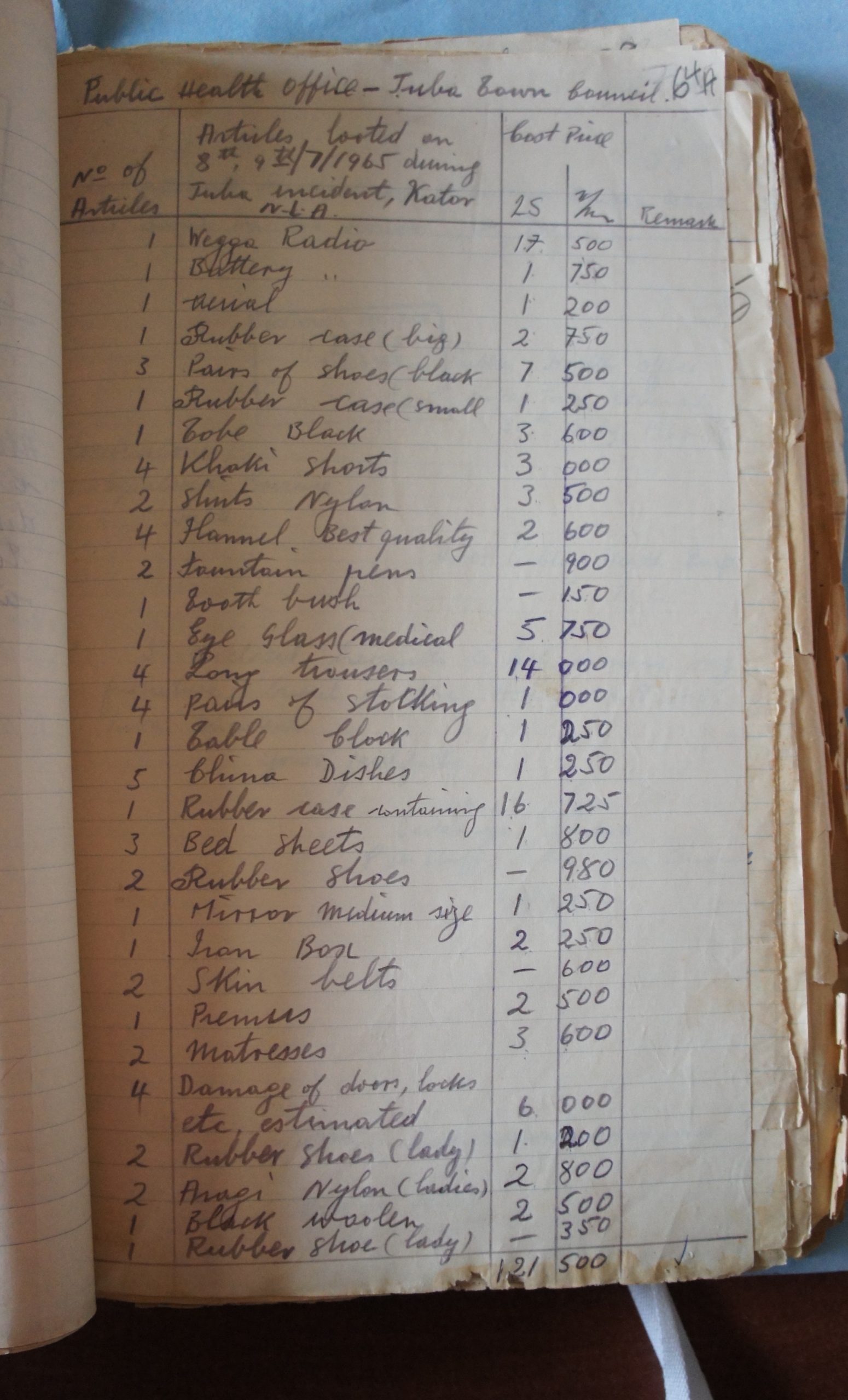

The file reveals that following the destruction in Juba, the government of Sudan offered a route for affected people to claim compensation for their losses. The terms of compensation were restricted. Only property was eligible for compensation and only individuals working for government would be considered for pay-outs.4 However, this relatively limited remit did not stop hundreds of people—even those who were not government employees—submitting claims for compensation. In their claims, individuals gave their names and occupations and listed their possessions which had been destroyed. Some of them included small notes, explaining the impact of events on their lives and livelihoods.

What do these claims reveal about the Juba Massacre and its impacts?

The most immediate insight from this file is the scale of the destruction. The official tally of claims submitted, finalised in 1970 by the Executive Officer of Juba Town Council, records that in Atlabara 447 people submitted claims following the destruction of their homes. In Kator, the number was 221.5 This amounts to at least 668 homesteads destroyed. It is certain that the real number was higher. Because the government had said it would only compensate government employees, many people would likely have been discouraged from claiming. Many others—including politically active individuals—had fled for safety in Uganda and rural areas and were no longer there to claim. From the list of professions, it is clear that a wide cross section of people working for the government were affected. Some individuals held relatively senior positions—such as senior information officers or head clerks. However, the majority had much more modest roles: a large number of drivers, messengers and school teachers were victims of the attack. These were professional people, but they were not necessarily the most privileged.

Beyond raw numbers, the individual nature of these petitions offers a glimpse into the personal impacts of the massacre. Someone who describes himself as a ‘petty trader’ sent a handwritten note to the Commissioner of Equatoria Province on 28 July 1965. It explained that he was disabled and had lost his livelihood following the destruction of 5 tukuls and the armed robbery of 75 Sudanese pounds:

Dear Sir, I would like to bring it to your notice during the 8 July 1965 disaster I had lost the following [5 tukuls, each built for 25 Sudanese pounds]. In addition to the above loses, 75 [Sudanese pounds] were taken from by (sic) a government soldier at gun point while trying to leave the burning home. Since I am a petty trader I cannot now carry on my trade because the money has been robbed besides that I am a lame person and cannot do any other physical work.

Another short note, sent to the Commissioner on 31 July 1965 reveals that the writer was also robbed, and that his daughter and her children had been killed.6

Stepping back from the details, one of the biggest revelations of the file is that Juba residents made these claims in the first place. Claimants must have had some degree of trust that they would be listened to and possibly even compensated by the government. They show a perhaps surprising amount of faith in the state, in the context of an escalating civil war. One senior clerk even wrote a follow up letter in November 1965, reminding the Chairman of the Equatoria Province authority that his compensation payment was due.7 Some people had a high degree of confidence that the government would indeed be forthcoming with compensation.

Beyond the direct effects of the massacre, these records provide unique evidence for the social history of Juba. Carefully transcribed lists of domestic artefacts and possessions paint a surprisingly intimate picture of urban life at the time. We learn what civil servants were wearing and what furniture they sat on. A clerk employed at the Police Headquarters goes so far as to list the contents of his library by name, giving us a glimpse into what a civil servant might have been reading in 1965. It’s an eclectic collection of 24 books, including the Bible, a history of Mahdist rule in Sudan and a novel intriguingly titled, ‘Dangerous Curves’.8

It is rare to find such detailed evidence of crimes like this—committed by state against an urban population—in an official document of this period. This file sheds valuable light on the character of massacre, the losses that were incurred and how the government dealt with the aftermath. While the file is revelatory, there are notable (and perhaps equally revelatory) omissions. Most glaringly, it leaves almost no trace of the lives lost in the massacre—estimated to be in the thousands. We can occasionally glean hints, for example in comments about a lost daughter and grandchildren, but there doesn’t appear to have been any official attempt to calculate the human cost of 8 July 1965.

Despite these caveats, this is a very important and powerful file. Official documentation will always offer a partial view of the past. Yet there are rich possibilities for deeper investigation, such as those recently undertaken into the 1992 Juba Massacre by the Juba Massacre Widows and Orphans Association, IJPS and the Likikiri Collective. For we have here one of those occasions, rare in South Sudan, where events that remain in living memory (personal or community) can be put together with official records and contemporary testimonies of the victims.

Notes

1. Akol Ruay, Deng D. ‘The Politics of Two Sudans: The South and The North, 1821-1969’. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala, 133-134.

2. Mills, LR. (1981) People of Juba: Demographic and Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Capital of Southern Sudan. University of Juba, Population and Manpower Unit. Research Paper No. 3. p.6.

3. For example, see coverage in The Vigilant newspaper, ’76 Southerners Slaughtered in Wau: plan to kill educated southerners started’ (14 July 1965)

4. South Sudan National Archives, EP 11 B 2/172

5. SSNA, EP 11 B 2/109-125

6. SSNA, EP 11 B 2/66

7. SSNA, EP 11 B 2/206

8. SSNA, EP 11 B 2/31