The Rift Valley Institute works in partnership with the Ministry of Culture, Museums and National Heritage (MoCMNH) on the preservation and digitization of the South Sudan National Archives. Under the current project, funded by the Government of Norway, through UNESCO, various activities are underway to showcase the information available in the archives to a wider audience. RVI and the MoCMNH are collaborating on a range of outreach activities including radio shows (Tarikh Tana), school study and discussion projects. and social media outreach.

Zoe Cormack is an anthropologist and a historian whose research focuses on art, material culture and the history of collecting in South Sudan. She has done extensive research in the South Sudan National Archives, and other archives and museums. She is working on a number of blogs, also published on her personal website, that draw on her archival research to contribute to efforts to demonstrate the rich diversity of information available in the South Sudan National Archives and the way in which that information can contribute to documenting South Sudan’s rich history.

This blog reflects on archival research into the construction of the grave of King Gbudwe in Yambio, carried out in the South Sudan National Archives. This is supplemented with recent photographs of the grave in Yambio, shared with me by Atem el-Fatih. Also included is some more recent (but very limited) information about the role of grave in local politics in Yambio.

***

Gbudwe Bazingbi (c.1835, also called Yambio) was a royal Zande leader and arguably the most prominent person in the recent history of the Zande people, who are resident in the central and western parts of South Sudan’s Equatoria regions. During his rule, he faced incursions from ivory and slave traders, Egyptian Government officials, officials in the Mahdia, British and Belgium forces—as well as participating in internal Zande wars. He was killed during a British patrol lead by Major Boulnois in February 1905.

There are different versions of Gbudwe’s death. The anthropologist Evans-Pritchard put together various accounts, based on Zande oral histories collected during doctoral research between 1926 and 1930. These suggest that Gbudwe was shot in the arm (and possibly thigh) when the patrol entered his homestead. He then shot three members of the patrol and injured a donkey that had been brought to transport him to the military post at Birikiwe (Yambio). In doing so, the British soldiers were forced to carry Gbudwe on a stretcher to a hut where he was put under guard and succumbed to his injuries. Some accounts suggest he died alone, others that one of his wives, a daughter of Tangili, was with him.1

The British version of events, captured in The Bahr el Ghazal Province Handbook, 1911 states:

An expeditionary force composed of four companies of the IXth and two companies of the Xth Sudanese, with detachments of artillery and mounted infantry, arrived at the village of the hostile Sultan Yambio on the 7th February 1905. The Sultan himself was wounded in endeavouring to escape, and died in hospital on the 10th idem.2

After his death, the Anglo-Egyptian military administration received intelligence that some of Gbudwe’s sons were planning an armed revolt and in January 1914, Mange, Basongoda, Mopoi and Gangura were sent as prisoners to Wau and on to Khartoum. With the exception of Basongodo, who died in Wau, they were eventually released and returned home.3

It appears that Gbudwe was initially buried in an improvised grave. Evans-Pritchard recounts that:

Gbudwe was buried at Birikiwe (Yambio) in a hastily dug and shallow grave, on which a was placed a pot. Some say that his head was left sticking out of the top of the grave and was covered with the pot. A Zande called Zai, who had held a minor commoner governorship, was buried nearby.4

Over time, considerably more care has been invested in the grave. At a certain point (date unknown) the grave was covered with stones in the traditional Zande style. Then, in 1948, two sons of Gbudwe added concrete to the stones to make the structure more permanent.

At this point, there was also an intervention from the colonial government in Gbudwe’s memorialisation. In April 1948, the District Commissioner of Zande District, Maj J.W.D Wyld wrote to the Governor General’s palace in Khartoum to request arrangements be made to produce to a plaque for the tomb in Yambio. Some care was taken over the aesthetics, Wyld requested it be made ‘either with some red stone to harmonise with the iron stone blocks, or grey to harmonise with the pointing.’5

The inscription itself read (in pa Zande):

Gbudue Bazigbi died in the year 1905. He was the Azande King here for many years. His other name was Yambio. The town was named after him. The former name for the town was Birekiwe (Forest of Thorns). His children Gangura and Zegi cemented his grave in memory of him in 1948.6

The text is a notably neutral interpretation of Gbudwe’s demise. He did not simply ‘die’ but was killed in a military patrol by British forces. A substantive part of the text is devoted to a description of Gbudwe’s legacy in the renaming of Yambio town. According to Zande oral accounts of the patrol against Gbudwe, Gangura and Zegi both played an active role in defence of their father against the British military force, but their role in this plaque is simply as refiners of the grave.7

We do not know who devised the words of the plaque. Was it the Anglo-Egyptian Government, retrospectively trying to sanitise their role in the death of Gbudwe? Or (this seems less likely, but still possible) was this text written by the descendants of Gbudwe, as a conciliatory gesture to the government following the murder of their father and their own exile to Khartoum?

We will probably never know, but whatever the motivations, it was the case that the Government made these arrangements and facilitated the plaque for Gbudwe’s tomb in Yambio, only a few decades after he had died at their hands.

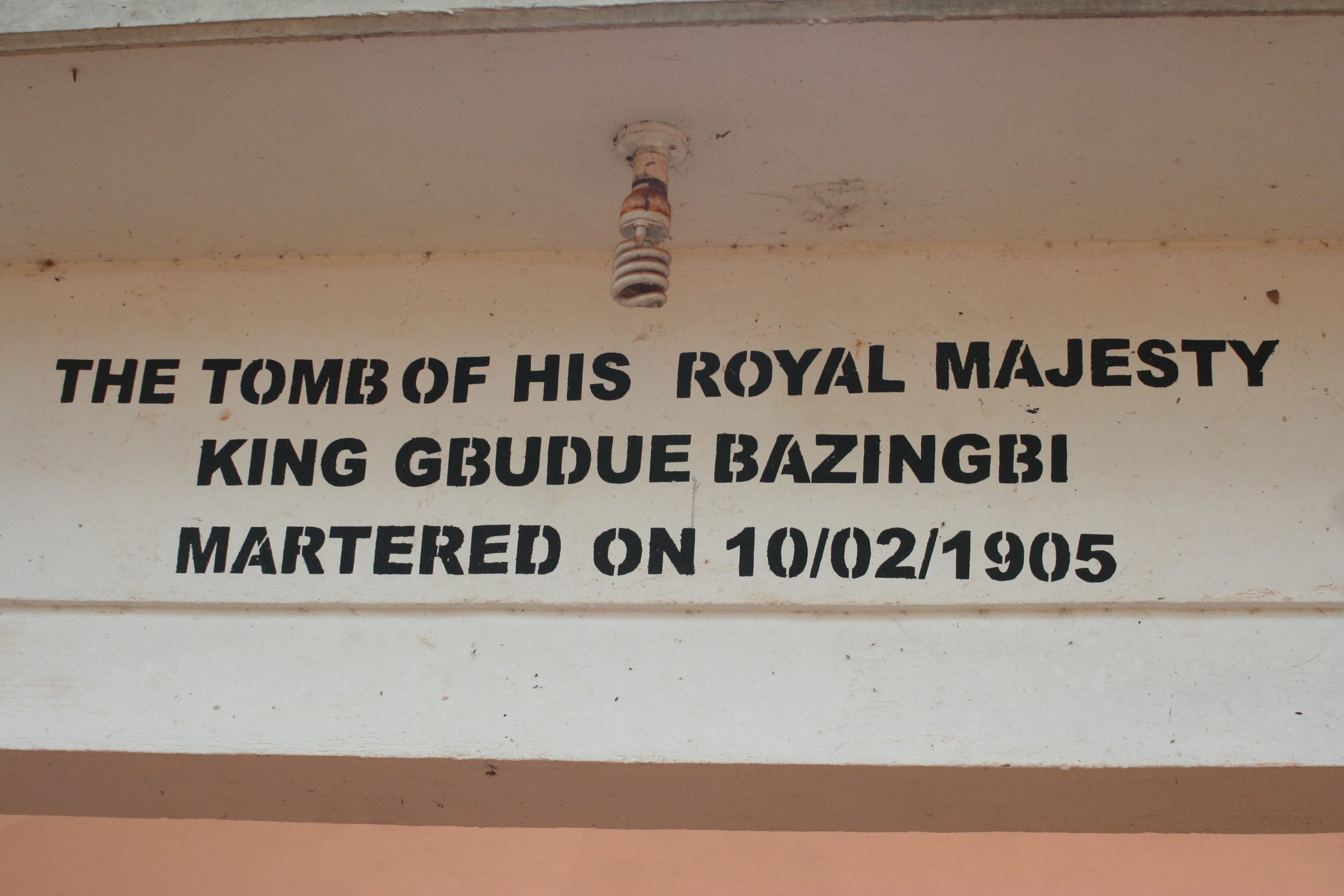

In contrast to what appears to be an overgrown site in the mid-twentieth century, the grave of Gbudwe in the twenty first century is more elaborate. A roofed structure was built over the grave when Jemma Nunu Kumba was governor of Western Equatoria State (2008-2010).8 The area around the grave has been paved. Two statues and several pots have been placed at the front. The area around the grave bore visible signs of maintenance when these photographs were taken in 2013. The old plaque is almost completely faded and a new inscription has been placed above the grave. It is much more explicit about the circumstances of Gbudwe’s death and identifies him as a ‘martyr’. It reads:

The tomb of his royal majesty King Gbudwe Bazingbi, martered (sic) on 10/02/1905

Reading across archival documents and more recent photographs, we can see how Gbudwe’s grave has been transformed and shaped by different (and sometimes surprising) actors.

The grave has become more elaborate and refined over time. But these changes have not been welcome by everyone. The Gurtong website states that there was opposition from the Mundu community to attempts to make the grave of Gbudwe a national monument in the 1970s:

Tradition has it that on his deathbed Gbudwe sent his army to kill and behead the Mundu king and to have the head buried with him. This has not been forgotten or forgiven by the Mundu that even in the late 1970s when the Azande wanted to construct the Gbudwe grave into a national monument officiated by the President of the Republic, the Mundu community in Yambio put up a stiff resistance and the ceremony was cancelled.

Today, Gbudwe has become a symbol of anti-colonial nationalism. The new description of him as a ‘Martyr’ at his grave ascribes him a place in the South Sudanese liberation struggle. For many Zande people his rule represents a golden era before the disruptions of colonisation and war. There have even been calls, including from Gbudwe’s great-grandson Wilson Peni Rikito Gbudwe, to reviving traditional authorities and the Zande Kingdom, of which Gbudwe was the last ruler.9 Around the time of South Sudan’s Independence, his grave in Yambio was the focus for some political events. The anthropologist S D Siemens reports that on 9 July 2011 the celebrations in Yambio:

began with an early gathering including the governor at the grave of King Gbudue…The congregants linked national independence with the sovereignty of the ancestral kingdom of Gbudue creating a continuity spanning a century of colonialism, war and neo-colonialism.’10

The memory of Gbudwe, and his grave, continues to be a dynamic focus for political aspiration and historical reflection.

Notes

1. Evans-Pritchard, The Azande: History and Political Institutions, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971, 391.

2. Cited in Evans-Pritchard, The Azande, 392.

3. Evans-Pritchard, The Azande, 394.

4. Evans-Pritchard, The Azande, 391.

5. National Archives of South Sudan (SSNA), Box ZD 63, File ZD 33 B1/1.

6. Zande text given in SSNA ZD 33 B/2 This translation was provided to Zoe Cormack via a Twitter user on 15/06/2017.

7. Evans-Pritchard, The Azande, 389.

8. This information was provided by Bruno Braak and Jackson Wani on Twitter 30-31/07/2020 https://twitter.com/BJBraak/status/1288794210532052992?s=20

9. B. Braak and J. J. Kenyi, ‘Customary Authorities Displaced: The experience of Western Equatorians in Ugandan Refugee Settlements, Rift Valley Institute, 2018.

10. S.D. Siemens, ‘Maquet’s Symbolic Participation and Diasporic Azande Identity’, International Journal of Anthropology 31/3 (2015): 89.