The people of Lakes State, in South Sudan–the majority Agar Dinka in particular–have the reputation among some other South Sudanese of being hot-blooded and short-tempered, a wild card in the wider Dinka confederation that constitutes South Sudan’s largest ethnolinguistic group. The Agar have been the subject of a number of anthropological and archaeological studies, but, until now, no book-length academic ethnography.

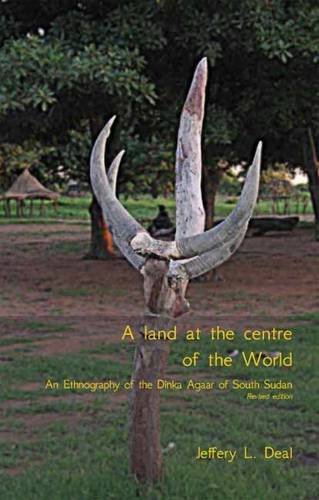

In the book under discussion here, A Land at the Center of the World[1] , Jeffrey Deal presents what he terms a “traditional” ethnography of the Agar for “those who would not otherwise read an ethnography”. His study focuses on Ticagok, a small market village in Rumbek East County of Lakes State. The nineteen chapters of the book, some of them only a few pages long, cover a wide range of topics including kinship and marriage, local politics and conflicts, HIV and health, religion, human rights, the law and the politics of aid, both secular and faith-based.

The book draws on anthropological fieldwork carried out when Deal was working as a physician at Ticagok Baptist Mission hospital intermittently between 2003-2009. He has amassed hundreds of interviews, surveys and photographs documenting life there in the years following the Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2005. This is a book that promises to show how a small rural community is emerging from civil conflict in South Sudan, shaped by the author’s aim that the reader should “feel engaged in the dialogue with the Dinka Agaar within a world where their lives and stories tell what needs telling”. The text is spliced through with lengthy quotations and excerpts from recorded conversations with informants.

‘An understanding of the dynamics of small rural communities is essential to those who come with agendas for conflict resolution’

These are issues of interest not just to academics, but to development practitioners and policy makers in South Sudan. A better understanding of the dynamics of small rural communities and their local politics is essential to the aid project, and particularly to those who come with agendas for democratization and conflict resolution. The Dinka are a key group in South Sudan: numerically dominant agro-pastoralists; their representatives form the largest ethnic group in the government. Deal presents a large amount of primary material on this Agar Dinka community. However, presenting the Dinka “in their own words” can create a misleading impression that these words offer the unmediated truth of what it is really like to be from Ticagok. Despite this implied claim, all texts are subject to selection and authorial control, no matter how extensive the quotation. Dialogue can conceal just as much as it reveals. Our understanding of Ticagok is not necessarily increased by this generous serving of direct quotation. And its uncritical presentation is the first sign of a deeper problem with this account.

Deal is oddly unengaged with other scholarship on the Dinka and South Sudan in general. The most frequently cited reference, for instance, is a 1908 article about syphilis in the Ugandan Protectorate. The discussion of kinship, paternity and cattle exchange does not have a single reference to Sharon Hutchinson’s well-established pioneering work on these aspects of life among the Nuer, a neighbouring people closely related to the Dinka. Idiosyncrasies and personal grudges frequently make their way into the text. Missionaries and NGO workers are described, for instance as “a plague of charlatans who preyed upon and added to the suffering of the sick and the lame”. The book is further let down by a large number of errors and inconsistencies in spelling (both English and Dinka). For example the Dinka term for inherited wife tiŋ a lɔ ɣöt is written as alohoot on one page and alhoout on another. This inattention to language affects even the name of the village at the centre of the study. In fact it is called Titagɔk, not ‘Ticagok’. The reference is to monkeys (agɔk) which used to gather at a mahogany tree (tit) in that location.

There are numerous errors in grammar and editing, which compound such inaccuracies. On one page a pseudonym is used for a former governor of Lakes State; on another his real name is used. Elsewhere Deal has eschewed pseudonyms; yet considering the sensitivity of many issues discussed, it might have been more ethical if he had used them. Particularly when he names a local chief and alleges that he regularly accepts bribes.

The opening sentence of the book betrays a startlingly odd assumption. Discussing the difference between outsiders and indigenes, he writes: “the most frequently recurring idea that separates us is the presumption that the Dinka are somehow guilty and deserve at least a measure of what they now experience”. What reader, one wonders, could possibly imagine that the problems experienced by the people of Ticagok–to return to the author’s spelling– are their own fault, that they deserve their misfortunes? Misfortunes that include two decades of civil war, with consequent poverty, lack of healthcare and education? Though he dissociates himself from this imaginary position, much of what Deal has to say about the Dinka is tantamount to an accusation of guilt. We are told in one chapter heading that the political organization of the Dinka Agar is “a recipe for corruption”, elsewhere that Dinka culture causes conflict and Dinka moral values make violence acceptable.

The recent history of Ticagok, as the author often reminds us, has been unsettled in the extreme. In 1994 it was virtually abandoned due to fighting between Dinka and Nuer, the result of a split in the southern rebel army, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army. Rumbek East County has suffered from intersectional fighting, botched disarmaments and local struggles for power and influence since the CPA was signed in 2005. In attempting to explaining why local conflicts occur, Deal blames the segmentary structure of Dinka society, extrapolating this to every society in South Sudan: “Personal vengeance was all that satisfied the delicate sensibilities of the tribes, families, clans, sub-clans and seemingly endless factions of South Sudan,” he writes. “This feature of South Sudanese culture creates an atmosphere of constant tension and the threat of violence.” This is a tautological explanation: it says that people fight because people don’t get on. Absent from the account are the consequences of the militarization of almost every level of society during the civil war, including the large-scale and often forcible recruitment of young people into the army. These are vital piece of the puzzle for understanding the ongoing local conflicts in South Sudan. But here they are presented, implausibly, as the inevitable consequence of Dinka social organization.

‘The explanation for acceptance of violence is not Dinka culture, but the brutality of civil war, and the hegemonic position of the army.’

Discussing the ethics of punishment and tensions with government authorities since the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005 Deal describes floggings and other brutal corporal punishments administered by a senior SPLA officer in Rumbek town and Rumbek East county in 2006. The SPLA officer ordering these punishments, who is here given the alias “Malual Kuat”, was brought in by the then governor of Lakes state in an attempt to improve security. He quickly became notorious. In Rumbek town, there was a tree known as the “BBC tree” where people gathered to discuss current events and criticize the state government. The BBC tree was felled by order of Malual Kuat and those gathered there, including a foreign aid worker, were beaten by soldiers.

Around the same time, in Ticagok, relatives of a number of people accused of the murder of a chief were arrested and beaten. Their only crime was to be related to someone suspected of murder. Deal would have us believe that both these acts of violence–the felling of the BBC Tree and the beating of those who gathered there and the beating of the relatives of the murder suspects–were viewed as appropriate actions by the people of Ticagok, because these acts of violence were carried out in accordance with local moral norms on collective punishment. Specifically, he argues that they conformed to the Dinka notion of cieng. Cieng has been discussed by a number of authors, including the Dinka scholar Francis Deng, as meaning something akin to moral order, the proper way of doing things. Deal uses cieng to connote the collective good; by allowing themselves to be punished by the government, he argues, the relatives of the wanted men were giving themselves up for the good of the greater whole. Everyone in Ticagok, according to Deal, thought this was an appropriate course of action.

This interpretation implies that extreme violence within the community is endorsed in Dinka moral and ethical codes–a doubtful conclusion. The application of the concept of cieng to SPLA brutality seems particularly inappropriate. The power wielded by the government and the army is of a different, extra-local order. It is not subject to the same moral code as the local community. A much more reasonable explanation of the apparent acceptance of the violence is not some inner essence of Dinka culture, but the brutality of a twenty-one-year civil war, and the continuing hegemonic position of the army in South Sudan.

Deal recognizes that civil war and developments in the years following the CPA have brought substantial social change in South Sudan. Security issues, youth and new livelihood opportunities are emerging as key challenges. Older patterns of livelihood based on cattle keeping are being increasingly problematized. In towns like Rumbek young people are searching out education to position themselves for the anticipated new opportunities following independence. In Lakes state this is reflected in (among other processes) complicated and sometimes strained relations between urban and rural cattle-keeping kin. Although Deal acknowledges the complexity of this situation, statements such as “their [cattle-keepers’] previously revered status is changing to one of shame and revulsion” do not do justice to the complexity of these debates about the future of pastoralism in South Sudan. Likewise, as local insecurity and disarmament remain key challenges in Lakes State and across South Sudan, scholars and practitioners who draw on ethnographic studies need to think far beyond the simplistic and essentialist explanations advanced in this book.

Zoe Cormack is a doctoral researcher at the University of Durham in the UK, studying agro-pastoralist communities in South Sudan. This essay was published by the Rift Valley Review in 2013.

[1] Jeffrey Deal, A Land at the Center of the World (Nottingham: Markoulakis Publications ISBN-13: 9780955747465).