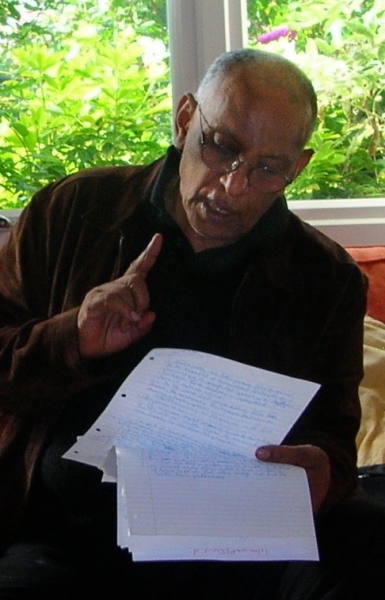

Tafari Wossen, an Ethiopian journalist and former civil servant, is the founding editor of the Seven-Day Update, a weekly news review published in Addis Ababa. This memoir of his childhood in the province of Waag was presented at the Institute of Ethiopian Studies at Addis Ababa University. It was published by the Rift Valley Institute in 2013.

I have lived through three eras in Ethiopian history: the final years of the feudal system, the revolutionary communist decades of the 1970s and 1980s, and finally the state-sponsored capitalist system of today. My childhood seems distant now, so much so that I sometimes wonder if it was real. But for my first decade the feudal system formed the limit of my world.

I was born in Waag in 1940, on May 9, in the heart of Ethiopia, son and heir of an hereditary feudal lord, Waag Seyoum or Wagshum Wossen Hailu. Although I was his son, I never called him “father”. Nor even “Wagshum”, which was his title. To his dying day I addressed him as “Getoch”, which means, literally, “Rich”, a form of address in Amharic that signifies “sir”, “lord”, or “master”. My father was a prominent figure in Ethiopia with a deep knowledge of our country’s history. To the Emperor, Haile Selassie I, bent on unifying the country and curbing the power of feudal leaders, he was a threat. And when I was quite young he was sent as Ambassador to Greece, a form of banishment designed to keep him away from Waag.

Waag–or Wag-Himra as it is now called–is still a remote place, on the border with Tigray to the north-east, Lalibela to the south and Ras Dashen to the west. At that time there was a no motor road and it was many days journey from the capital. I was raised in Sekota, the main town in the area. It was an unusual upbringing. I saw little of my father and hardly remember my mother. (I was separated from her at a very early age and don’t even know when she died.) The task of bringing me up was left to the patriots–the elders and war veterans of Waag–and to an Italian named Romano Gino.

By age of three, in accordance with my position in the feudal hierarchy, I was made a Mislene, or viceroy. This was a position that my grandfather and his father before him had occupied. I had a monthly salary of 30 birr. There was a person who acted as my guardian and ran the day-to-day affairs and for that, he took half of the salary.

To prepare me for the full assumption of my responsibilities at future date, I was instructed in a number of traditional roles. I used to sit in court. I visited prisons to inspect and to release a few prisoners by granting them pardons. Every Sunday and there was a special place for me in church, or else I would take my father’s place. In Sekota, I attended church service at Medhanialem Church, built by Wagshum Teferi Wossen in 1893, where the remains of my grandfather and great grandfather had been laid to rest. I was taught how to shoot and ride a horse. People were constantly around me guiding me on what to do and say, and the right way to behave.

If Romano raised his voice against me, the soldiers would go for their guns to shoot him. And I would rush to protect him

My father also arranged for me to be introduced to modern life and the world outside Sekota. This was the task of an Italian named Romano Gino, who my father had rescued from death at the hands of the patriots of Waag during the Italian occupation. (He appears in Beatrice Playne’s memoir St George for Ethiopia as “the Italian doctor”.)

During my childhood in Sekota, I lived with Romano Gino in a building that belonged to my father after it was taken from the Italians. It had been a pharmacy during the Italian occupation of Waag. When he was in town my father stayed in another building where the Italian Commander had lived. And I had the run of the old supply depot of the Italian army across the street. It had almost everything: exercise books, pencils–and guns. There was a bicycle left behind by the Italians. Strangest of all, there were hundreds of boxes of condoms. I used to make balloons out of them. No one told me not to. I think no one in Sekota knew what they were for, except Romano Gino.

I lived, effectively, in a military garrison. The war was over, but the patriotic forces of Waag who had fought at my father’s side had not yet been dispersed. I was not allowed to go out of the compound without an escort; or to play with other children, except those who were invited to visit me. Wherever I did go, fifty or more guards would accompany me.

I lived, effectively, in a military garrison. The war was over, but the patriotic forces of Waag who had fought at my father’s side had not yet been dispersed. I was not allowed to go out of the compound without an escort; or to play with other children, except those who were invited to visit me. Wherever I did go, fifty or more guards would accompany me.

I used to speak Italian in those days, and learned how to read and write Italian before I knew how to do the same in Amharic. I don’t remember speaking Agewigna or Tigrigna, although many people in Waag did–and still do. I clearly recall praying in Italian, and showing off to my father whenever he came to Sekota. My father spoke Italian perfectly and I used to write letters to him in Italian, signing them “Tafari Romano”.

Romano taught me table manners, how to use a knife and fork, and how to eat spaghetti (which I still eat now and then). He had clothes brought for me from Italy or Asmara. My clothes were changed every day, sometimes twice a day. I had tooth brushes and tooth paste. Sixty years ago in Sekota these things were an unheard of luxury; even today they are rare.

Romano was more of a father to me during my childhood than my own father was. But he was still regarded by some in Waag as an enemy alien. If he ever raised his voice or his hand against me, the soldiers who guarded me would go for their guns as if to shoot him. Then I would rush to protect him by standing in front of him. I never knew if they really would have fired or not.

Because of my traditional position and upbringing, I learned to be polite and courteous to my elders. Sometimes this was through hard experience. One day I gave a mock salute to my favorite Kegnazmach. My father saw me and punished me severely for my insolence. On another occasion, I beat a boy with a whip. My father heard about it. The boy and his father were called in and he apologized to them. Then he handed the whip over to the boy to hit me the way I had hit him. The boy declined, so my father did it himself in front of them, without mercy.

The young patriots of Waag would ask me what I was going to do for them when I grew up and how I was planning to reward them for their loyalty to me. It was expected of me to say to them that I would make them a Dejazmach, or a Fitawrari, or a Kegnazmach, the feudal titles widespread in Ethiopia, or name them governor of a certain area, or give them houses, or guns, or gold. They never doubted that one day I would become a Waag Seyoum, and that I would honor my word. I remember how much of a burden that felt. As it turned out, history, in the form of the Derg regime, deprived me of these powers, sweeping away the system of titles and feudal privilege, delivering both me and them from obligation.

I often travelled between Sekota and Korem, a distance of a hundred kilometers or so. These trips were determined by whether my father was in Addis Ababa or in Korem. It was then a two-day journey by mule or foot. The roads built by the Italians had been destroyed in early 1940. The route was mountainous, with lush green vegetation. We always had an entourage of a hundred or more, carrying guns. Bandits, or shiftas, haunted the forests. Some bore a grudge against my father; others were just out for robbery. We carried no supplies; villagers gave us food.

I was determined not to be a stranger to my country again.

My father used to tell me that the people of Waag were like misir (lentils), meaning that they stayed together, as close as kinsfolk. But his own ability to serve them was curtailed in 1950 when he was made Ambassador to Greece. This was a form of banishment, in order to remove him from his sphere of influence in Waag. My father never saw his home again. The Emperor never allowed him to return. And in 1951 I was sent to school in England. Although I loved England, it was not home. And I returned to Ethiopia in 1963 as soon as I could, without consulting my father. My father himself died in 1984 without ever seeing Waag again, even during the Derg period.

Given my ancestry, many people are surprised that I did not go abroad when the revolution began in 1974. I think the reason was because of my childhood experience and my long stay in England. Readjustment to the new realities of the country was tough in the first few years. The world I knew as a child was swept away. But I was determined not to be a stranger to my country again.