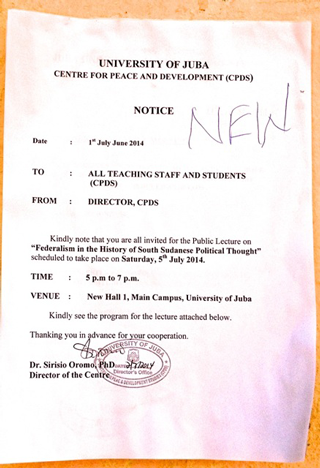

More than seven hundred people attended a lecture on federalism at Juba University on Saturday 5 July. The lecture was delivered by Rift Valley Institute Fellow Douglas H. Johnson and organised by RVI Fellow Luka Biong Deng, formerly Minister in the Office of the President. Dr Johnson’s talk was introduced by John Akec, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Juba. Panellists included Lam Akol, Chairman of the Sudan Peoples Liberation Movement-Democratic Change. Journalists, dignitaries, students and others filled the lecture hall to overflowing, with many listening through the open windows.

In the wake of the political crisis which has plunged South Sudan into civil war again, a debate about future forms of government is gathering speed. The idea of federalism in particular has become highly controversial. The debate has been complicated by the military conflict. On one side, as Dr Johnson explained, SPLM-IO (the Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement In Opposition) has adopted federalism as a political platform. On the other side, the government has violently denounced the idea, seeking to suppress coverage in the media and discussion in public fora, with some officials suggesting that discussion of federalism itself amounts to political disloyalty.

Dr Johnson argued that there needs to be open discussion among South Sudanese citizens so that people are able to understand what federalism might mean and decide whether or not they support it. He traced the history of federalism in South Sudanese politics from the 1954 Juba Conference to the present day, contrasting debates before Sudanese Independence in 1955—which pitted federalism against self-determination for the South—with later schemes of decentralisation under Nimeiri, which he termed ‘federalism lite’.

‘If we are to learn anything from the past history of South Sudanese political thought,’ Dr Johnson said, ‘it is that federalism means many things’

Historically, Dr Johnson noted, before the separation of the two Sudans, a federal system of government was presented as the only constitutional arrangement that could guarantee a united Sudan. By the advent of the Second Civil War (1983-2005), however, the idea of federalism had been replaced by that of devolution. Both were then effectively abandoned by Southerners in favour of self-determination. In South Sudan federalism is now advocated for a host of reasons, from a purported guarantee of government accountability to an expedient way of removing political enemies.

‘Until there is a full and open discussion of the issue,’ he concluded, ‘there will be no common understanding of what federalism might mean for South Sudan, and once understood, whether the majority of South Sudanese will want to adopt it.’

The lecture was followed by a wide-ranging debate. Daniel Zingifuaboro, the Western Equatoria State Minister for Local Government and Law Enforcement argued—in a personal capacity— for a federal system, contrasting it to decentralization. In the latter, he said, power is passed downwards from the central government to the people. In a federal system, however, power moves upwards from the people through local and state government to the central authorities and is therefore more representative. Federalism, he added, is concerned with the division of territory, not of people.

Dr. Jaafar Mori, the Dean of the College of Social and Economic Studies, presented results from a opinion survey conducted among Juba University students. The overwhelming majority of students from Greater Equatoria and Greater Upper Nile, he said, preferred a federal system of government, while students from the Greater Bahr el-Ghazal region favoured a presidential system. Thus, he argued, South Sudan ought to be governed by a system combining both that he termed presidential federalism.

Augustino Ting Mayai, Director of Research at the Sudd Institute, argued that the issue of federalism had less to do with the system of government selected by the people than with its implementation. Both the interim and transitional constitution of South Sudan provide for a federal system, he argued, and the present system of government was already federally decentralized. What was lacking was the implementation of constitutional provisions.

Lam Akol, Chairman of the SPLM-DC, pointed to problems with the country’s transitional constitution, and the limited representation on its drafting committee of those outside the ruling Sudan Peoples Liberation Movement. Federalism, Dr Lam argued in conclusion, is a more inclusive system of government—and one which will ultimately serve the citizens of South Sudan best.

Following the meeting newspapers in Juba that reported the event were confiscated by Government security forces. According to a report in the Sudan Tribune security operatives raided the premises of the independent Citizen newspaper, confiscating all its Monday edition. The paper’s editor-in-chief, Nhial Bol Aken, said: ‘They took all the 3,000 copies because we covered federalism debate.’