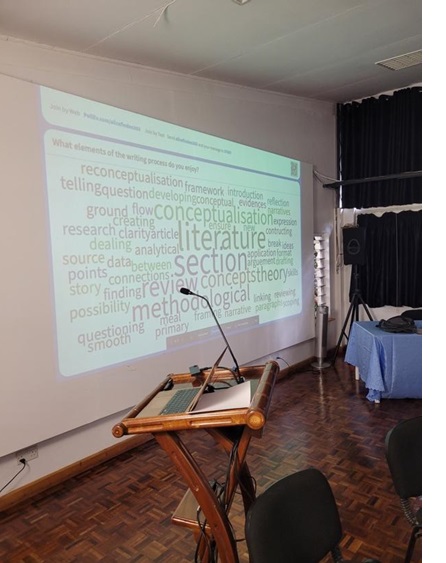

This blog reflects on the academic writing experiences of early career researchers in East Africa, building on discussions and writing diaries developed in the context of a British Academy-funded Writing Workshop in Nairobi (Kenya), in February 2024. The workshop encouraged participants to develop writing diaries, observing their writing practices, identifying achievements and challenges, and taking account of the affective atmospheres and emotions that accompany the practice of writing.

Seven of the 15 participants have subsequently shared their diaries with the organisers who have started to engage in an iterative writing process with the participants. The blog is an outcome of our joint reflections on academic writing. We have created a main protagonist, an author named Gelizako Juwiva Chrinjalinya (Gelizako),[1] who will in the following share their experiences and thoughts. The creation of Gelizako ensures the anonymization of experiences but especially aims at de-individualizing academic writing. We discuss the motives for creating Gelizako and introduce them in the first section. The other sections engage with the embodied writing experiences of Gelizako, focusing on its affective, communicative, and institutional aspects. We conclude with a discussion on the vexation of academic writing.

What Is an Author? It is an Gelizako Juwiva Chrinjalinya

When Foucault (1969) asked his famous question What is an Author, he explored the modern creation of authors as individual producers of texts. Accordingly, authors become unreflective of the heterogeneous nature of their individuality as they display a relation of externality to their finalized writing product. Ironically, due to prevailing academic norms, the very subjectivity of these authors is then buried in the academic product and disappears.

We created Gelizako as a countermove to this type of authorship. Gelizako, who prefers the pronoun they, is not a mere average of twelve individual authors but was created to emphasize the iterative process that went into writing this blog, and which is – as we discuss below – characteristic for academic (and other) writing. Writing itself is often experienced as a solitary activity, requiring a retreat and exclusion from social activities. Writing, as Gelizako emphasizes repeatedly, needs focus and concentration, which they can only find in solitude. Whenever they can, Gelizako ‘lock [themselves] in the office’[2], go to a quiet place in the library, or sit in a café where they feel undisturbed and are ‘able to concentrate.’

While discussing their writing practices and taking notes of them in the diary, however, Gelizako also realizes that ‘writing is a process of communication’ – composed of engagements not only with people, but also, as they will further elaborate below, with the wider, nonhuman environment, among them plants, animals, and other things. Like the writing of the diary, which Gelizako used to observe themselves – academic writing is at the same time personal, relational, and collaborative, crossing spatial and temporal barriers.

Writing as Embodied and Affective Engagement

Reading the diary, Gelizako finds that their writing is imbued in affects and gives rise to a multitude of emotions. They, for example, find inspiration from readings, but are also affected ‘in unexpected ways’ for example, by ‘listening to music’, ‘watching a documentary’, ‘walking the streets’, following ‘discussions and debates on Twitter’, or discussing ‘with friends.’ Gelizako, nonetheless, finds it quite difficult to start a paper. They noted in the diary that the sheer ‘magnitude of the work […] can demotivate, […] it seems as though it is a very huge task which cannot be accomplished. For example, when [we] have an article or report that [we] must write, and it is like 15 pages […], at first […], it can be humongous and scary to embark on.’

Fear is a crucial part of Gelizako’s writing. Sitting in front of an empty paper is especially scary. After all, they aim at ‘expressing the deepest of [their] thoughts and the wealth of [their] intuition’ and they are expressing it ‘for others’. Thus, while Gelizako may write in solitude, the possible readers are already in their minds, and with them come all the feelings of self-doubt and fear.

Writing also comes with a feeling of responsibility, and Gelizako sometimes doubts that they give the right message. In a recent paper on Motherhood, for example, they question ‘What are we putting out there? Do we want legal frameworks to guide motherhood that is generating this Mamaism?’ They do not want to contribute to the stereotype of Mamaism that is prevalent in their society and Gelizako’s everyday life. Instead, they want to critique the ‘social and gender norms [that] are expecting women to be mothers’ constructing them as ‘humble, obedient, submissive, and accepting all forms of oppression.’ Will they achieve this, or will they rather sustain existing norms? After all, writing is not only a bodily and emotive experience, but we also write bodies into our work in different – gendered – ways.

Academic writing is structured and densely policed by institutional requirements and scientific norms, many of which feel like strait jackets, obligations one must fulfil. The norms provide the more experienced parts of Gelizako with security, as they have already learned how to incorporate them. They already have been disciplined in the academic writing process, but self-doubt comes up nonetheless. The less experienced sides in Gelizako are often looking anxiously at the big unknown of the writing journey, and doubt that they are up to the task and can manage it.

Uncertainties about their ability to write academically as well as doubts about the substance and effect of their writing are rampant. In this sense, ‘writing for academic purposes is both thrilling and frustrating, involving days or weeks in front of a laptop, playing with words, only to realize the result lacks fascination or publishable quality.’

But when Gelizako are confident about their topic, when the views of other authors are aligned to and support what Gelizako wants to write, and when the audience is expected to benefit from the writing, then Gelizako feels happy, and the writing flow eases. This points to the continuous communication and engagement with others that shape the seemingly solitary process of writing and produce many of its emotions.

Writing as a Communication

Writing involves an engagement with the writing of other authors – some living or writing about issues far away, others in different times or even epochs – a type of communication that defies linear temporalities and Cartesian spatial orders. The articles and books that are piling up on our desks, filled with our notes and scribbles (albeit this engagement increasingly takes a virtual form), attest to the multi-temporality and spatial messiness of our writing. Gaining access to these books and articles, is often an issue for Gelizako, as some of their universities cannot penetrate the paywall of the academic journals and books Gelizako desires to read. Difficulties with ‘obtaining the relevant scholarly information’ or accessing much-needed databases, discourage and demotivate Gelizako.

Gelizako also tries to share their work with others drawing them into a relationship with the reviewer. When their writings ‘resonate with the reader’ and when they ‘get positive compliments’, Gelizako ‘feel excited’ and ‘happy’. Critique can also cause initial frustration but does not necessarily discourage Gelizako as they know that it can improve their writing, facilitating self-awareness, learning and development.

However, the author-reviewer relationship is often asymmetrical and onerous, especially when institutional structures and societal and academic norms perpetuate inequality. Gelizako remembered one incident where they presented their proposal and a professor remarked ‘“you girl, stop confusing us’’. Oh, that was a destructor, not the message but the concept. [We] started thinking about why he couldn’t refer to [us] by [our] name, he knew all the names, he could have shortened the names at least if they were very long, and he could have called [us] student if the name escaped his mind.’ Gelizako is aware of the literature on the power differences and often gendered nature of feedback and peer review (Mandalaki 2024). The comments of the professor nonetheless hurt, as they deface and make them invisible. They make Gelizako feel unable and worthless.

Breaks and Self-Care

Writing also requires the author to recharge and regain motivation and energy. This involves a series of intervals, breaks, ruptures, procrastination, and planning. Sometimes Gelizko finds that ‘reading can be boring and draining especially when [we] do it late in the evening or when [we are] feeling exhausted, but if [we are] reading at the start of the day, [we are] more focused and [we] find reading interesting.’

This also entails recognising the body’s fragility and limits and caring for our bodies by prioritising rest and leisure. For Gelizako ‘rest is always another motivation […], especially when [we] get some thought blocks, and I cannot progress with the writing.’ At times, motivation and drive come from taking the time for ‘sports, travel, and literature.’ Turning the mind outwards to gaze and watch[3] – nature walks and Netflix – emphasises how writing is not necessarily an inward-oriented activity but draws from the world outside.

Institutional and Other Constraints

The worlds of authors are complex worlds of multiple identities and institutions. The latter can be both enabling and constraining. Gelizako’s academic institutions do not always incentivize research and writing, and many early career scholars have a high teaching load which together with administrative duties take ‘a big toll of [their] time and energy’. They do not always get a fixed salary, or sometimes their salary is not enough to accommodate the needs of their family, and they, therefore, also often take on paid consultancy work, not all of which they find interesting. Authors are of course more than researchers. Family commitments, especially for early career academics with young children, take a lot of planning and negotiation. Gelizako reflects in the diary: ‘we are a parent of 4 children who drives my children to school on a daily basis and collects them in the evening. So given that they are still young (oldest is 10 years) this is also quite tiring.’ Gelizako also mentions ‘distractions while writing that can come from family when someone delivers a message about a sick person, and you have to pause’. This has been a learning curve in that they ‘have learnt to switch off the phone and be off social media.’

Conclusion: The vexation of academic writing

Gelizako’s diaries reveal how writing is simultaneously shaped by solitude and communication. It is emotive, influenced by uncertainties, and embedded in institutional norms and wider social relations. Writing links Gelizako to people in different places and times, and it links them to the objects, materials and subjects that surround them.

Various critiques of academic writing have highlighted the formalistic, constraining, and disembodied processes of knowledge production that continue to be the formally and informally acknowledged norms of scholarly writing. These limitations have been profoundly addressed in feminist scholarship, as well as through other aesthetic and affective modes of writing which prioritise the relational, ethical, and indeed, political dimensions of writing and knowledge production (Mandalaki 2024). Moreover, there have been numerous calls to write differently, especially in feminist work, which often means writing freely in a way that is unencumbered by the narrative structures of academic style, especially concerning the rigidity and demand for objective knowledge (Dide van Eck, Noortje van Amsterdam, and Marieke van den Brink 2019).

The above complexities and challenges that underpin academic writing, we suggest, can be conceptualised through the notion of vexation as elaborated in Judith Butler’s work on giving account of oneself. In her theory of subject formation, Butler (2005, 36) notes that narration – i.e., the act of giving account of oneself – ‘takes place within a structure of address’ in which the narrative authority is often shaped by certain entanglements, temporalities, and norms. The relationality that underlies this process and the exposure (i.e., vulnerabilities and uncertainties) it encompasses constitutes this idea of vexation. This conceptualisation allows us to explore the narrative structure, relationality and subject positions that shape knowledge production through writing and speaks to the embodied process Gelizako identified. Writing, so they tried to show, is relational, affective, and both enabled and constrained by institutional rules and societal norms that carry with them social inequalities and signs of domination.

These relationships of power can and are being challenged. By moving beyond the focus on the different approaches and ways of writing, decolonial interventions identify the Western epistemic groundings of knowledge production which shapes the nature and purpose of writing, as well as the agencies that animates these processes. For decolonial scholars, decolonising academic writing as such involves a ‘huge political, moral, ethical and epistemological shift’ (Trashar et. al 2019, 158). This involves acknowledging – and embracing – uncertainty, vulnerability, openness, and experimenting with new forms of writing and knowledge production. Along this line, academic writing entails writing differently from different epistemic registers, imaginings, and experiences including those from the Global South. Powerful critiques of Western stereotypes, including Dipo Faloyin’s Africa is Not a Country, ‘not only provide an engrossing adventure for the mind but also trigger deeper reflections.’ Gelizako’s reflections add to these registers, bringing vexation to the fore but also optimism and enjoyment. Gelizako ultimately finds the act of writing ‘interesting given the fact that you are expressing the deepest of your thoughts and the wealth of your intuition for others to have the same experience,’ a process ‘that is both thrilling and frustrating’.

The authors

Innocent Ayesiga, Jutta Bakonyi, Nyasha Samuel Chikowero, Kodili Chukwuma, Alice Finden, Elizabeth Katusiime, Jacqueline Nakaiza, Geoffrey Lugano, William Musamba, Eva Maria Nag, Christine Olukhanda, Sekito Zaid

Top photo by Suzy Hazelwood. Others photos, authors’ own.

[1] The name is a composition of some letters of all the authors first names: Geoffrey, Elizabeth, Zaid, Kodili (Gelizako); Jutta, William, Eva (Juwiva); Christine, Innocent, Jaqueline, Alice, Nyasha (Chrinjalinya). The idea to create the figure of Gelizako Juwiva Chrinjalinya was derived from an EWIS (2024) workshop paper by Andrew Neal and Christian Buerger entitled Ruins and Futures: An Adventure in Infrastructure in the Shetland Islands; and by the comments of Andreas Langenohl who discussed the iterative character of the person.

[2] If not stated otherwise, all direct quotes are taken from the diaries of workshop participants.

[3] Gelizako made the photo gazing out of the window during the writing workshop.

This blog post first appeared on the Global Policy blog. The piece was co-authored by Geoffrey Lugano, Research Communities of Practice Programme Manager at the Rift Valley Institute, colleagues from Durham University and participating students as part of the British Academy Writing Workshop hosted by RVI.