Key points

-

Nairobi’s Eastleigh neighbourhood hosts one of the largest ethnic Somali communities outside Somalia—composed of Kenyan Somalis as well as Somali nationals whose numbers have swelled since the collapse of their state.

-

Eastleigh has become an important centre of Somali diaspora life and a hub for a trust-based trading community that operates across East Africa and into Asia and the Middle East.

-

With the rise of al-Shabaab, Eastleigh’s Somalis—already stereotypically associated with refugees, illegal immigrants and the piracy, corruption, and crime that beset Somalia—are now often associated with terrorism.

-

In 2014, in the wake of al-Shabaab attacks in Kenya, the Kenyan Government targeted Eastleigh in a massive security sweep. Thousands were detained and an estimated 500 were deported.

-

The Somali presence in Eastleigh remains controversial, with many questioning the right of Somalis to live outside the refugee camps.

-

Somalis in Eastleigh, many of whom are Kenyan by birth and descent, resist their narrow stereotyping as interlopers in Kenya and as agents of terrorism and continue to assert their right to live and work in the neighbourhood.

Participants

Tabea Scharrer, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology

Neil Carrier, University of Oxford

Dr Ibrahim Farah, University of Nairobi

Hon Yusuf Hassan, MP for Kamukunji, Nairobi

Hannah Whittaker, Brunel University

Lucy Lowe, University of Edinburgh

Mark Yarnell, Refugees International

Joseph Wandera, St. Paul’s University

Willem Jansen, St. Paul’s University

Ahmed Mohamed, Eastleigh Business Community

Lul Issack, UMMA CBO

Salah Abdi Sheikh, Author

Solomon Masitsa, Kituo cha Sheria

Pauline W. Kamau, Kenyatta University

Keren Weitzberg, University of Pennsylvania

Hanna Elliot, University of Oxford

Holly A. Ritchie, Erasmus University

Hassan Kochore, National Museums of Kenya

Jacob Rasmussen, Roskilde University

John Mwangi Githigaro, St. Paul’s University

Gianluca Iazzolino, University of Edinburgh

Introduction

On the weekend of 27-28 of September 2014, the Rift Valley Institute Nairobi Forum hosted ‘Eastleigh and Beyond: The Somali Factor in Urban Kenya’ at the Rift Valley Institute office in Nairobi. The conference was organized by Tabea Scharrer (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology) and Dr Neil Carrier (African Studies Centre, University of Oxford).

Showcasing a wide variety of work from established and upcoming scholars, human rights practitioners, community leaders, local politicians and business people, the conference considered the complicated place of ethnic Somalis in Kenya. Discussants examined current controversies such as the growing presence and influence of Somalis outside the refugee camps, stereotyping and marginalisation in the wake of terrorist acts by Somalia-based al-Shabaab, the growth of Somali businesses, and the links of the Somali diaspora with a globally expanding Islamic network of trade and discourse. The conference took as a point of departure the Nairobi neighbourhood of Eastleigh, which hosts a large Somali population. Over the past two decades, the Somali community has transformed the neighbourhood into an important East African trade hub and a centre for the Somali diaspora. As result, it has become an emblem of Somali-ness in Kenya and a site of economic, political, and cultural contest between Somalis and other Kenyan communities.

The Honourable Yusuf Hassan, Member of Parliament for Nairobi’s Kamukunji Constituency and the first Somali to be elected MP in Nairobi, opened the conference. He gave an overview of the history of Eastleigh, his own experience of change in the neighbourhood, and some of the challenges the neighbourhood’s residents face. Emphasising the diversity and dynamism of Eastleigh, he described its evolution from a residential neighbourhood for Indian and Pakistani communities under the British Colonial administration to the bustling multi-cultural neighbourhood it is now. Yusuf Hassan explained that as the meeting point for a variety of national and transnational networks, Eastleigh has a substantial influence on the Kenyan economy and is also an important religious and educational centre for the Somali diaspora. However, attacks in Kenya by al-Shabaab have made Eastleigh the focal point of a security campaign that has indiscriminately targeted ethnic Somalis. MP Hassan welcomed academic attention to Eastleigh as an opportunity to cast a different light on a Nairobi neighbourhood often simplistically associated with refugees, radicalisation, and illicit trade.

The Honourable Yusuf Hassan, Member of Parliament for Nairobi’s Kamukunji Constituency and the first Somali to be elected MP in Nairobi, opened the conference. He gave an overview of the history of Eastleigh, his own experience of change in the neighbourhood, and some of the challenges the neighbourhood’s residents face. Emphasising the diversity and dynamism of Eastleigh, he described its evolution from a residential neighbourhood for Indian and Pakistani communities under the British Colonial administration to the bustling multi-cultural neighbourhood it is now. Yusuf Hassan explained that as the meeting point for a variety of national and transnational networks, Eastleigh has a substantial influence on the Kenyan economy and is also an important religious and educational centre for the Somali diaspora. However, attacks in Kenya by al-Shabaab have made Eastleigh the focal point of a security campaign that has indiscriminately targeted ethnic Somalis. MP Hassan welcomed academic attention to Eastleigh as an opportunity to cast a different light on a Nairobi neighbourhood often simplistically associated with refugees, radicalisation, and illicit trade.

Urban aspirations, exclusion, and the war on terror

Participants noted that ethnic Somalis in urban Kenya are popularly assumed to have entered the country illegally or to have migrated from refugee camps in the north of the country, despite the fact that ethnic Somalis form a large part of Kenya’s indigenous population. The presence in Nairobi of large numbers of Somalis has thus raised questions about who has the right to be in the city. Many, as Hannah Whittaker (Brunel University) noted, perceive Somalis as temporarily encamped in Nairobi, which has conceptually limited their claims to place in the city. Yet Somali claims in Nairobi can be traced back to the early colonial period. Whittaker’s research revealed that the first Somali settlers arrived in the city during in the early days of the colonial administration’s racial zoning of Nairobi. Although they were perceived as nomads and livestock traders and therefore not ‘natural’ urban-dwellers, they actively negotiated their resettlement with the authorities, stressing their law-abiding and hygienic behavior in order to gain some influence in the selection of their place of settlement. According to Whittaker, their agitation was not just an expression of political demands, but also a manifestation of an urban aspiration that continues with recent Somali efforts to settle in urban areas.

A predominant theme of the discussion was the conflict that has emerged between the Somali community in Eastleigh and Kenyan state security agencies in the wake of increasing terrorist attacks on Kenya by al-Shabaab. Participants referred frequently to 2014’s Operation Usalama Watch in which Kenyan security forces swept through Eastleigh, detaining thousands of Somalis and deporting many. On several occasions the issue was framed in terms ‘agency’, as a contest between Somalis in Eastleigh seeking to assert agency over their own lives while the government attempts to restrain and exclude them. Several discussants argued that security crackdowns like Usalama Watch drive people underground and force them to develop tactics to avoid the state. They cited evidence that despite deportation and relocation initiatives, Somalis, including refugees, reappear in Eastleigh and other urban centers quickly. Discussants suggested that this speaks to both to the porousness of camp borders but also to the adaptive resilience of the Somali community’s state-avoidance techniques.

A number of participants raised concerns about the status and rights of refugees in the context of security crackdowns. Mark Yarnell (Refugees International) argued that Operation Usalama Watch has been a major setback to the advancements of refugee rights. Citing Somali refugees in Eastleigh who describe the camps in strong terms—‘Dadaab is like a cage’; ‘We are treated like animals’—Lucy Lowe (University of Edinburgh) argued that Kenyan encampment policies serve to prevent local integration and to preserve refugees in an extended state of limbo. However MP Hassan argued that Kenyan refugee law is not unique and that encampment is a common policy across Africa. He stated that refugees and urban businessmen have violated that law, and the fact that the state has permitted them to do so has added to confusion about the status of the law.

Identity, status, and belonging

Issues of identity, formal status, and belonging were repeatedly evoked in presentations and discussions. Keren Weitzberg (University of Pennsylvania) described the changing imagination of Somali-ness in relation to the Kenyan state. She drew from statements by Jimali Adbi Raheem (‘We want to be part and parcel of this nation)’ and from Al Jazeera’s Mohamed Addow (‘We are not migrants, we are not from another country’) to argue that, since independence, there has been a trend among ethnic Somalis in Kenya away from identifying closely with Somalia towards identifying with Kenya. Weitzberg argued this represents a move towards more transnational forms of belonging, where many claim Kenyan-ness while still maintaining associations with the wider Somalia region.

The difficulty of getting—and getting by without—official status was an oft-cited issue. Several practitioners, such as Solomon Masitsa (Kituo cha Sheria), noted the insecurity that arises from the lack of clear refugee policies. Ahmed Mohamed (Eastleigh Business Association) told how refugees struggle to become Kenyan citizens. Lul Issack (UMMA) described the desperation that occurs when refugees have asylum applications turned down. And Holly Ritchie (Erasmus University) pointed out how difficult the business environment can be for refugee women who, without access to banks and financial institutions, are limited to petty trade.

Gianluca Iazzolino (University of Edinburgh) highlighted the importance of clear official status—as a refugee, student or national citizen. He pointed out that the more documents one has, the better one is able to relate to and operate with the state in which one resides and with the wider world. He presented his study of Somali refugees in Uganda. Uganda, he said, has a relatively progressive refugee act that emphasizes protection. It gives Somali refugees access to ID cards, allows freedom of movement and of association, and recognizes Somali passports. Iazzolino stated that there is now even a small group of Somalis in Uganda lobbying for acceptance of Somali as an official tribe in Uganda. However, he pointed out, it is not lost on some Ugandans that the liberal policy towards Somalis may be building a new constituency of support for President Museveni.

Gianluca Iazzolino (University of Edinburgh) highlighted the importance of clear official status—as a refugee, student or national citizen. He pointed out that the more documents one has, the better one is able to relate to and operate with the state in which one resides and with the wider world. He presented his study of Somali refugees in Uganda. Uganda, he said, has a relatively progressive refugee act that emphasizes protection. It gives Somali refugees access to ID cards, allows freedom of movement and of association, and recognizes Somali passports. Iazzolino stated that there is now even a small group of Somalis in Uganda lobbying for acceptance of Somali as an official tribe in Uganda. However, he pointed out, it is not lost on some Ugandans that the liberal policy towards Somalis may be building a new constituency of support for President Museveni.

Uses and abuses of ethnic stereotyping

Several discussants raised the issue of stereotyping of Somalis as interlopers in Kenya and, since the spate of al-Shabaab attacks, as agents or supporters of terrorism. Their discussion cast light on the various presentations and uses of stereotypes of Somalis in the wider Kenyan political discourse.

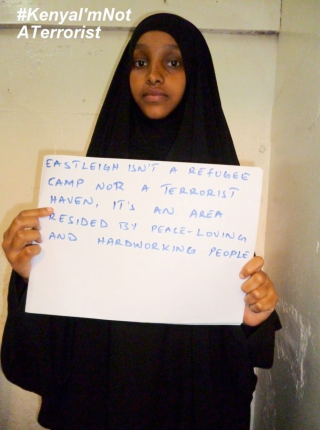

Willem Jansen (St. Paul’s University) described ethnic profiling during Operation Usalama Watch—noting that some in Eastleigh re-named it ‘Usama Watch’. Lul Issack remarked that the one-sided representation of Somalis as terrorists leaves them vulnerable to abuses, stating that the Kenyan security forces who extort money from Somalis under threat of arrest have come to refer to Somalis as ‘ATMs’. One Somali Eastleigh resident commented: ‘We are captured and sold back to our own people’. Muna, a social worker and activist from Eastleigh, gave an illustration from Eastleigh youth who protested Operation Usalama Watch through a photo-campaign, with images showing young Somalis holding the words ‘Kenya, I am not a terrorist.’

Lucy Lowe reflected on the self-reinforcing dynamic of fear the current situation has created, in which Somalis become afraid of working with non-Somali Kenyans and non-Somali Kenyans become afraid of Somalis, further entrenching ethnic profiling. Holly Ritchie and Ahmed Mohamed related that in this atmosphere of fear, many victims of violations do not pursue claims, despite the strong work of Kenyan NGOs. MP Hassan argued that what happened Eastleigh was not ‘Usalama Watch’ (which translates as ‘Peace Watch’), it was an ‘Eastleigh sanitation campaign’.

Joseph Wandera (St. Paul’s University) and Halkano Abdi Wario (Egerton University) presented their analyses of how Somalis and Operation Usalama Watch had been represented in different media. In one daily paper, the discourse has changed over time, from presenting Somalis as rogue suspects of terrorism towards eventually also presenting them as victims of human rights abuses and police brutality. In contrast a Muslim weekly bulletin immediately reported on human rights abuses and proffered rationales for the operation beyond merely security concerns – raising the possibility that stereotyping of Somalis both facilitated and masked a variety of interests at work. In keeping with this analysis, Tom Wolffe (Synovate) questioned the timing of Operation Usalama Watch and the motivations behind it: Did it relate more to electoral politics, or to an upcoming rally organized by the opposition Orange Democratic Movement? Was it an excuse to raise police budgets? Was the growing business dominance of Eastleigh the target?

Communities of trust: the expanding reach of Somali trade networks

On the second day of the conference, the conversation turned to the growth of Somali business networks, for which Eastleigh is an important centre. MP Hassan pointed out that the neighbourhood is often referred to as ‘Little Mogadishu’—a nickname he said lends strength to the perception that Eastleigh’s economy is based on pirate money, human trafficking and money laundering. Yet panellists called attention to the paradox that although business in Eastleigh is popularly associated with lawlessness, it is based very strongly on personal trustworthiness. Other discussants described their findings that despite all the negative connotations associated with Somalis and Eastleigh, there is also a common perception that Somali businessmen are honest and that a deal with a Somali businessman can generally be relied upon.

Panelists suggested that the system of trust on which the Somali business community operates is perhaps best exemplified in hawala. Hawala is a unique system of money transfers based on trust, rather than on formal law or contracts, that is operative throughout the Somali diaspora. John Mwangi Githigaro (St. Paul’s University) described how remittances from abroad sent via hawala have further generated Somali diaspora trust-based business partnerships.

Panelists suggested that the system of trust on which the Somali business community operates is perhaps best exemplified in hawala. Hawala is a unique system of money transfers based on trust, rather than on formal law or contracts, that is operative throughout the Somali diaspora. John Mwangi Githigaro (St. Paul’s University) described how remittances from abroad sent via hawala have further generated Somali diaspora trust-based business partnerships.

Hannah Elliott and Neil Carrier talked about their exploration of Somali business networks and reported that trust relationships have superseded clan and lineage relationships, as is evident in the incorporation of Somali businesses in global Islamic business networks. Neil Carrier commented that many Somali commercial ventures are linked to businesses in the Gulf, noting that faith-based trust is a gateway to greater business opportunities from the wider Islamic world. Hannah Elliott argued that as a result, there is a trend towards traders valuing Islamic identity over clan identity. Holly Ritchie observed that trust is perceived as an important element of Islamic character so that a person regarded as a devout Muslim is also regarded as trustworthy. Other participants commented that the Somali/ Islamic trust networks are drawing in other communities that do business with Eastleigh—examples were given of Meru and Oromo traders who have converted to Islam and learned to speak Somali in order to prove their trustworthiness.

Closing the day, Tabea Scharrer noted that the same model of business seen in Eastleigh—based on money flows through trust-based networks and manifesting certain multifunctional configurations of space associated with a lack of regulation—has appeared where Somali businessmen operate in Nakuru, Kampala, and even in Johannesburg. She argued that although the Eastleigh model is often touted as an example of unregulated free market competition, the presence of trust networks and the hawala system of money transfer shows something deeper: economic competition creating opportunities for new loyalties and networks, as well as for profit.