On Wednesday 29 November 2017, Eye Radio and the Rift Valley Institute aired the fifth and, for now, final radio show in the South Sudan National Archives radio series, in coordination with the South Sudan Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports and UNESCO, with Norway’s financial support.

The show was hosted by Clement Wani Cirisio and looked at a document preserved through the work of the National Archives, ‘The functions of the leopard-skin chief’, an extract from the draft manual of Nuer customary law commissioned in 1944 by the colonial authorities.

The speakers invited to discuss the historical context of this document and the role of traditional leaders in South Sudan were Dr Gabriel Riam, a specialist in Nuer traditions, Mr Deng Nhial Chioh, an anthropologist and heritage expert and Mr Jacob Jiel Akol, a journalist and writer, who phoned in from abroad. Mr Opoka Musa from the National Archives joined the show to talk about his work as an archivist for the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports.

The speakers invited to discuss the historical context of this document and the role of traditional leaders in South Sudan were Dr Gabriel Riam, a specialist in Nuer traditions, Mr Deng Nhial Chioh, an anthropologist and heritage expert and Mr Jacob Jiel Akol, a journalist and writer, who phoned in from abroad. Mr Opoka Musa from the National Archives joined the show to talk about his work as an archivist for the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports.

Mr Nhial explained that the term leopard-skin chief was an incorrect translation of Kuaar Muon, which means ‘earthly custodian’ in Nuer. ‘They put the word Chief there, which is not correct,’ said Mr Nhial. ‘The office of Kuaar Muon is very independent and very unique, he’s a peace maker and a mediator, he can profess some curses, and whenever a person kills another person, [that person] will run to Kuaar Muon.’

‘Kuaar Muon in the Nuer governing system is a very important person,’ said Dr Riam. ‘He has inherited powers in which he has the role to intervene when there are problems that may bring conflicts among the people.’

These inherited powers, and the mediating role in conflict resolution, are similar to the functions of another traditional leader in South Sudan, the Dinka Spear Master.

Mr Cirisio played a recorded interview with Mr Jacob Jiel Akol on this matter. ‘As I wrote in my book “I will Go the Distance”,’ he said, ‘quoting the case of my grand father who was a Spear Master or Master of the Fishing Spear, they have the power of blessing and cursing in arbitration of any dispute … The Spear Master is acknowledged as the true traditional leader in the Dinka community. His roles are blessing as well as curses. Spear Masters will bless people going to war and also be able to curse those who are attacking them. Among the Dinka clans, they are the elite of the society.’

Back in the studio, the speakers described how Kuaar Muon can curse those who disobey his or her orders, for instance by threatening them to become infertile. He can also ‘pray for a family to get peace or for a woman to get a child.’ But, Mr Nhial stressed that ‘Kuaar Muon is not a kudjur [witchdoctor] nor a prophet … but a peace maker and a mediator.’

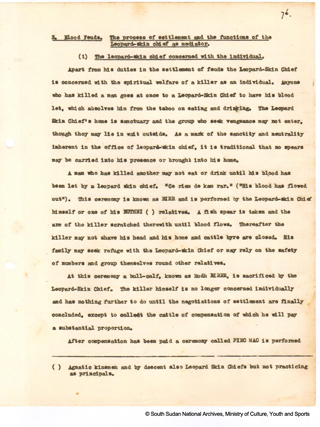

Dr Riam described a ritual called birr, mentioned in the archive document. ‘When somebody is killed, Kuaar Muon is obliged to receive the person who has committed the crime and he will have to cut his or her blood out. He mixes it with a clay, pours some water, and that person drinks it. Now that person becomes free from the taboo [of eating and drinking]. If that function is not performed, that person is going to die, according to the Nuer tradition.’

How can such a ritual prevent retaliation and revenge killings, asked the journalist?

‘When a person runs to the house of Kuaar Muon,’ explained Dr Riam, ‘it becomes like a sanctuary, like a prison. Nobody will come near to that person. It means that the person who has committed a crime is protected … His or her relatives receive a message, they are alerted, so that they will take care of themselves.’

After performing the birr ritual, ‘Kuaar Muon will initiate a dialog between the person who has killed a person and the relatives of the deceased. He will make sure that something immediately happens. He will go on talking to them and that is how the conflict will be resolved. If he is resisted, this is where the question of curses will come in, he will use his spiritual powers to say, “if you violate this, this will happen to you” … The communities of the two parties will be involved to resolve the conflict. Once that is done, there will be a normal procedure that will be done, like blood compensation.’

Both guests admitted that, although ‘Kuaar Muon still exists in certain areas and even here in Juba,’ according to Dr Riam, the description of this ritual and method of conflict resolution largely belonged to the past. The colonization and promotion of the new role of Chief (Sultan) by the British took away some powers from the leopard-skin chief. Successive wars as well as an increasingly urban lifestyle also contributed to this loss of influence of such traditional leaders.

However, the speakers stressed that Kuaar Muon was a figure that all South Sudanese can learn lessons from.

‘In the Nuer community, when there is blood feud, people cannot eat together, they cannot talk together, until that ritual is done. So in the country now, we need that spirit. People should come together and be birr [cleansed] and then they reconcile … So this is where people can make peace because everybody will confess that “I did this, I did this and I did this.” So this is the kind of reconciliation that used to happen with Kuaar Muon.’

Dr Riam insisted that ‘South Sudanese people have to refer back to their own traditions if they want to have peace … If we use the resources that we have, then we can be able to dialog with our hearts open and confess.’

‘That’s the importance of heritage, of the cultures as a way of resolving problems,’ said Nhial. ‘But when you have left your culture, your system, then you fall apart … What we need to do now in South Sudan, we need to think through the archives because these documents are very vital, [to bring] peace and heritage values to South Sudan,’ concluded Nhial.

The archivist Opoka Musa explained the next step in the development of the South Sudan National Archives involved the digitization of the documents and the training of the archives staff in all the states of South Sudan. ‘Being an archivist, I’m very happy with the developments that have taken place on the National Archives, with the help of UNESCO and the Rift Valley Institute … We have come a long way since 2011 to make the Archives viable.’ He mentioned how a government official requested to see a specific document in order to verify some information. Opoka was able to retrieve the document easily, because, as he said, ‘we have arranged it in a way that makes it is very easy to trace documents … That means we are moving forward’ he said, ‘because the National Archives is a place where you get the right information.’

RVI is also working on a larger project looking at the changing role of customary authorities in South Sudan, which you can read more about here.